The Wine Aroma Wheel

Joy Ting

January 2020

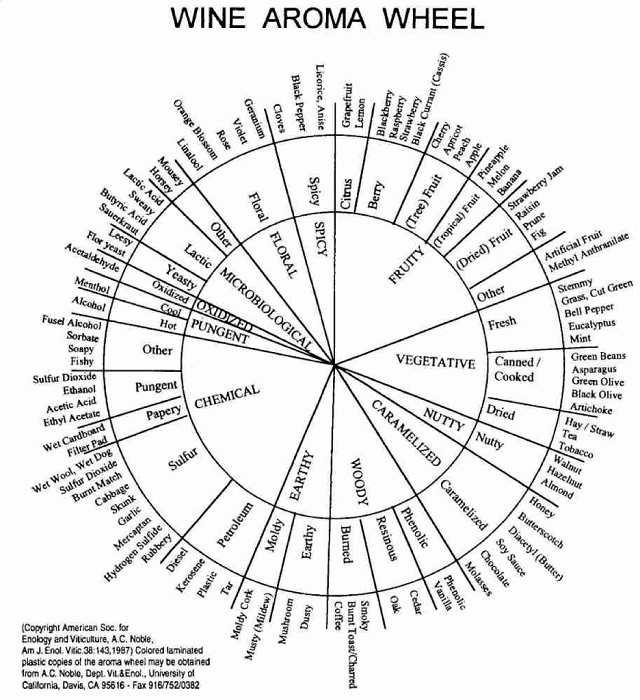

“The tool that transformed wine tasting”1, the Wine Aroma Wheel, was developed by Dr. Ann Noble and her colleagues at UC Davis at the request of the Sensory Evaluation Sub-committee of the American Society of Enology and Viticulture in the early 1980’s1,2. First developed for academic audiences, by 1990 it had become so popular with wine critics and consumers that laminated versions of The Wine Aroma Wheel were being sold at wine shops and through mail order. (These are still available today, currently listing at about $10 on Amazon.) The Wine Aroma Wheel remains a valuable tool for wine sensory analysis and training, and the story of its development provides an excellent case study in the development of a sensory lexicon.

At the time, people didn’t have good terminology for describing wine. Rather, they tended to use nonspecific terms (“elegant”, “masculine”), leading to difficulties in communication. The Wine Aroma Wheel was developed to aid communication among members of the wine industry including winemakers, marketers, researchers and wine writers, with specific emphasis on communication between winemakers and cellar staff as well as winemaker understanding of the academic literature2. As Ann Noble herself said “How can you even evaluate your own wine against others if you don’t use the same words?”1.

Like any lexicon (a word bank for a particular topic), the Wine Aroma Wheel began with a list of “virtually all possible wine descriptors”1 compiled from student laboratories, wine critical reviews, published papers, and other sources1,2. Then the list was refined. Hedonic or subjective terms were removed. An effort was made to include terms that were as specific as possible so that each separately identifiable aroma or flavor was represented by a descriptive term2. A questionnaire was sent to over 100 wine professionals to gauge the relevance and potential use of the terms*1,2. The first version of the wheel was published in 1984 and included a solicitation for readers to comment on the list and make suggestions. Like any good lexicon, it was open to refinement2. A second version was published in 1987 and included some re-organization for easier use, elimination of infrequently used or redundant terms and the addition of the “nutty” category. It was at this time standards were also suggested for the terms found in the third tier3. This modified version of The Wine Aroma Wheel remains in common usage.

Several characteristics of the Wine Aroma Wheel make it a useful tool even today. The hierarchical presentation (adopted from wheels already in use for beer and whiskey) organized 119 terms in three tiers to allow similar specific odors to be grouped together under 29 more general categories3. This organizational structure aids in searching for terms, while still allowing more general terms to be used if a more specific term is not appropriate. Second tier terms are often used by wine critics, consumers, and marketing personnel4. Though third tier terms are already very specific, they can also be combined (apricot-peach) if needed2.

References standards were proposed for each of the third tier terms in 19873, and standards have now also been formulated for the second tier terms5. In both cases, an effort was made to avoid chemicals that are difficult or expensive to purchase, and those that degrade quickly, instead favoring readily available items that can be found at the grocery store (such as fruits and vegetable), winery (oak flavor), or outdoors (cut green grass). Instructions are readily available for standard preparation and include adding foodstuffs or other reference materials to a base of either a neutral wine (free of defects with low intensity aromas) or a blend of water and neutral spirit. After 30 minutes, the aromas should be apparent and useful as references3,5. Comparison back to the base wine helps detect the effect of a spiked aroma.

Since the publication of the wine aroma wheel, several specialty wheels have also been produced, including wheels for sparkling wine, Brettanomyces, and mouthfeel. Recent studies exploring the effect of training panelists on standards to the second tier of the aroma wheel shows that training leads to better alignment around common terminology, fulfilling the original intent of this project, improving communication among wine professionals.

Reference standards are easy to prepare and use. There are several practical ways you can use these standards during cellar or tasting room training to improve sensory expertise.

*Only 70 of these 100 questionnaires were returned, a good reminder of the importance of responding to inquiries; these folks missed the opportunity to weigh in on what would become the standard terminology of wine. Consider this a friendly reminder to return your Grape Report every year.

References

(1) Teague, L. The Tool That Transformed Wine Tasting. Wall Street Journal. 2020.

(2) Noble, A. C.; Arnold, R. A.; Masuda, B. M.; Pecore, S. D. Progress Towards a Standardized System of Wine Aroma Terminology. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 1984, 35 (2), 107–109.

(3) Noble, A. C.; Arnold, R. A.; Buechsenstein, J.; Leach, E. J.; Schmidt, J. O. Modification of a Standardized System of Wine Aroma Terminology. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 1987, 38 (2), 143–146.

(4) Joseph, C. M. L.; Albino, E.; Bisson, L. F. Creation and Use of a Brettanomyces Aroma Wheel. Catalyst: Discovery into Practice 2017, 1 (1), 12–20.

(5) Bowen, J. T. S.; Cantu, A.; Lestringant, P.; Sokolowsky, M.; Heymann, H. Wine Sensory Reference Standards to Align Wine Tasters on a Shared Terminology. Catalyst: Discovery into Practice 2018, 2 (2), 42–49.