Randomized Complete Block Design for Vineyard Experiments

Joy Ting

May 2020

Vineyards are variable places. We think about this when it is time to select a site, decide which varieties get planted where, how to fertilize or what (if anything) to grow between the rows. It is also crucial to consider the variation in the vineyard when setting up a vineyard trial or doing fruit sampling. Data analysis and interpretation are only as accurate as good experimental design allows, so it is crucial to consider the scale of each treatment and the physical and temporal plan for sampling before starting.

The main issue when setting up a vineyard trial is minimizing the differences between treatemens that are due to environmental effects in order to be able to recognize any differences that are due to the treatment itself (1). The solution to this challenge is replication, both in the treatment regime and in the sampling regime. If the treatment is applied in multiple places in the vineyard and shows the same effect each time, it is more likely that effect is due to treatment than simply because it occurred in a particular location in the vineyard.

Figure 1 from The Low Down on High Yields, Skinkis, 2017

The randomized complete block design is a common method for setting up trials in the vineyard. Three main components contribute to the strength of this approach: blocking, randomization and replication (1).

A “block” is a defined, relatively homogenous region of the vineyard that is subdivided to receive each level of treatment. Several blocks are identified within the vineyard as replicates, with each block receiving each treatment level. Within each block which region receives which treatment is assigned randomly. Randomization reduces the bias that would be introduced by having a pattern of assignment.

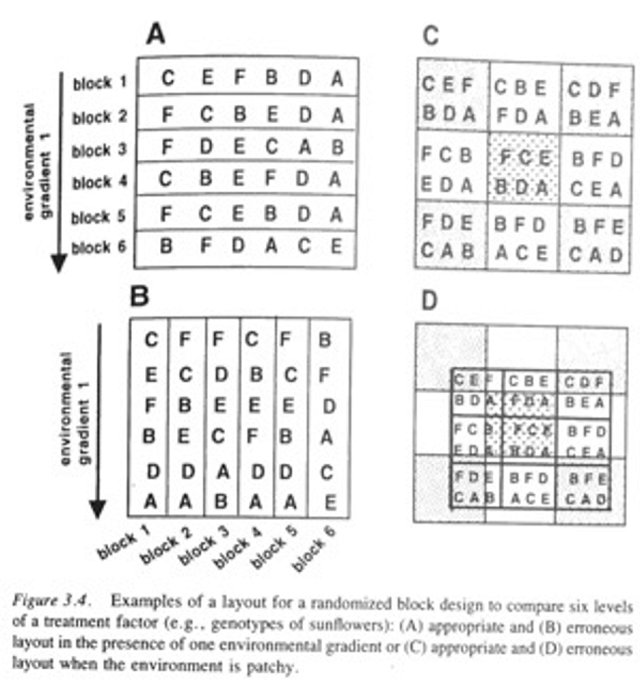

When setting up the blocks, it is important to take the overall layout of the vineyard into consideration. The size and location of each block is determined by the level of environmental heterogeneity. Heterogeneity within the block should be very low while between block heterogeneity can be large. For example, a vineyard located on a slope should have a block that contains each treatment on the top and another block at the bottom of that slope rather than treatment at the top and control at the bottom. Figure 3.4 from Design and analysis of Ecological Experiments(1) provides a good visualization of these issues.

Figure 2 from Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments, Scheiner, 1993

Another level of variation occurs during sampling. Any time a vineyard is sampled, there are a range of values that could found based on the variation that is present in that vineyard. Within a single grape cluster there can be berries with a wide range of sugar values, so it is unlikely a single berry can be chosen to represent the whole cluster. To narrow the value as close to the actual value as possible, good sampling must be practiced. This includes taking care to collect a representative sample, avoiding the biases of picking the most obvious or most attractive fruit. Many guides are available to ensure samples come from different locations on the vine and different locations on the cluster (2–4). However, sampling can also be in error due to environmental variation. Replicated sampling within a block (at the near, middle, and far portion of a row, for example) can help tease out variation due to location vs. variation due to treatment level. A key element to keep in mind while sampling for a vineyard trial is that the sample is not meant to determine the overall level of any metric for the whole vineyard, but rather it is meant to minimize environmental variation to determine differences due the treatment level. Individual sampling at multiple places sum together to determine if these changes are consistent throughout the vineyard.

By carefully selecting treatment blocks placed at multiple sites within the vineyard, and collecting replicate samples within a block, statistical analysis can then be used to separate which portion of the variation is due to the block location, the treatment level, and just random chance (1). Setting up the vineyard experiment with these elements allows much more clear interpretation of the data and a much better chance of accurately identifying treatment effects.

References:

(1) Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments; Scheiner, S. M., Ed.; Chapman and Hall, Inc: New York, 1993.

(2) Zoecklein, B. W. Grape Sampling and Maturity Evaluation for Growers https://www.apps.fst.vt.edu/extension/enology/VC/Jan-Feb01.html (accessed Oct 30, 2019).

(3) Wolf, T. K. Wine Grape Produciton Guide for Eastern North America; Plant and Life Sciences Publishing: Ithaca, New York, 2008.

(4) Amerine, M.; Rossler, E. B. Field Testing of Grape Maturity. Hilgardia 28 (4), 93–114.