Representative Vineyard Sampling

Vineyards are variable places. No matter how well you sample the vineyard, it is still a sample; you will never know for sure based on a sample what the true value is. Any sample you take has a range of accuracy depending on the amount of variation in the vineyard, the variety, and the vintage. As you design your sampling scheme, it is important to be aware of the types of variation that matter most, and account for those in the sampling plan to obtain the most representative sample. There are several layers of variation to take into account as you sample.

The first thing to consider is whether the vineyard is relatively homogenous or not. Zoecklein (Enology Notes 53) says that the three things that make the most difference in maturation are heat, light, and soil moisture. If you know you have an area that will ripen differently due to disease, aspect, or other factors, make sure you incorporate this area in the correct proportion. Alternatively, you could sample this area separately, but add it back to your normal sample in the correct proportion. Also, if there has been a frost event and the vineyard is split into primary and secondary clusters (as in 2020), sample separately and recombine in the proportion found in the vineyard.

In addition to large spatial differences, there are also smaller scale differences to be aware of. Ripening maybe different based on:

- Exposed vs shaded areas on the vine

- Opposite sides of the row

- Different parts of the vine (close to the trunk, middle of the cordon, end of the cordon)

- Different parts of the grape cluster

- Edge effects: Avoid end vines and perimeter rows

Sampling bias can also be a factor in the accuracy of a grape sample. As humans, we tend toward a bias of picking grapes that are most apparent, and most ripe. To minimize the effect of sampling bias, it is good to have a methodology for sampling that includes intentional sampling in a way that takes this into account.

Practically, what does this mean?

The instructor for my Davis classes suggested following a prescribed method to keep yourself accountable:

- Take a berry from every 10 vines in the row, alternating sides.

- Skip rows so you cover the whole block; if you make 4-6 passes alternating sides, you have sampled 8-10 rows

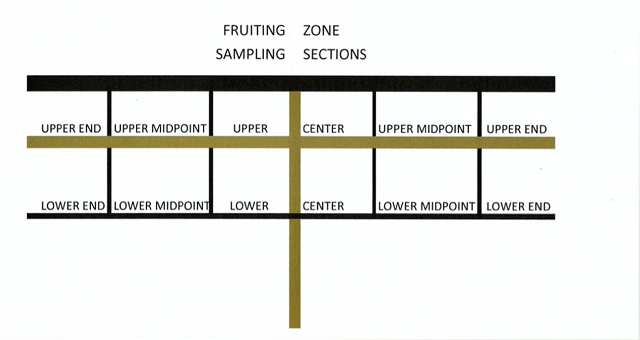

- Think of the different sections of the fruiting zone of the vine. If you have upper and lower clusters, and center, midpoint and end, sample these in order each time: Upper End, Upper Middle, Upper Center, Lower End, Lower Middle, Lower Center. Amerine and Roessler (1958) found that 90% of variation in a berry sample is due to variation in the position of the cluster on the vine and degree of sun exposure.

- Also, think about the parts of the cluster. Top, middle, and bottom, front and back. These grapes can all contribute to variation. That same professors suggested a “modified cluster sample” to reflect the differences found within the cluster: taking one berry from the top, one from the bottom, then successive berries as you burrow to the middle of the cluster in the center. This would mean taking 7-10 berries from one cluster on a vine, but still allow you to sample from a wider range of vines in the vineyard.

When sampling, consider the different regions of the grapevine. Amerine and Roessler (1958) found that 90% of variation in a berry sample is due to the position of the cluster on the vine. (UC Davis Vineyard Sampling 2016.

Berry vs. Cluster vs. Sentinel vine sampling

Amerine and Roessler (1958) compared three sampling methods: berry, cluster, and sentinel vine sampling. When they compared the results of berry samples (100-200 berries), cluster samples (10 clusters each) and whole vine harvesting, they found they all averaged around the same mean Brix level. However, the variation between samples was least for berry samples and most for whole vine samples. This means that the range of possible answers when they sampled these 10 times was wider for whole vines and clusters than berries. They concluded that sentinel vine sampling is best for uniform vineyards and clusters are best for varieties that are known to have large variations within clusters, but berries are most appropriate for most varieties.

Zoecklein (Enology Notes 54) recommends the following guidelines for sampling size:

- Within 1 degree Brix: 2x100 berries or 10 clusters

- Within 0.5 degree Brix: 5x100 berries (no cluster number is given)

Ultimately the best way to determine the sampling method that is most accurate for your vineyard is to do both types of samples just before harvest, and see which is most accurate once the harvest comes in. Sounds like a great experiment!

References:

Determining Grape Maturity and Fruit Sampling, Ohio State University Extension, 2014

Enology Notes #53, Bruce Zoecklein, 2002

Field Testing of Grape Maturity, Amerine and Rossler, Hilgardia 28:4 p93-114

UC Davis Wine Production (VID252), Vineyard Sampling module, 2016