Tannin additions to build structure in red wines

Joy Ting

November 2018

When wines lack body and structure, manufacturers often recommend the addition of tannins. To aid in the decision of whether to add tannins or not, and which tannins to add, this section describes tannins in general, the role they play in aging, and when you might want to consider using this tool.

According to Jackson (2014), tannins are “polymeric phenolic compounds that can tan (precipitate proteins) in leather; in wine they contribute to bitter and astringent sensations, promote color stability, and are potent antioxidants”. If we look back to Zoecklein’s equation for palate balance:

Sweet <-> Acid and Phenols

we can see that tannins (polyphenolic compounds) shift the weight of the equation to the right. Ribereau-Gayon and Peynaud (1997) developed a wine suppleness index that can be defined as:

Suppleness= Alcoholic degree – (total acidity + tannin level)

Both of these equations indicate that some tannic astringency is needed to balance the sweetness that comes from fruit and alcohol in wine.

During fermentation, the tannins are the slowest portion of the phenolics to accumulate, requiring time spent on the skins and seeds for full extraction (Jackson 2014). Many of the wines this year were made with limited maceration times to avoid extracting harsh tannins, and to avoid microbial spoilage. This may lead to lack of structure needed to balance this equation.

In addition to adding structure to the wine, there are other reasons to consider the addition of tannins. Tannins bind to anthocyanin molecules, stabilizing color, and bind oxygen, acting as an anti-oxidant. They also bind aldehydes, allowing for recovery of slightly oxidized wines. Under the right circumstances, tannin can react with oxygen as part of a polymerization reaction that recycles the oxygen-reactive portion of the molecules, providing long term antioxidant protection for the wine (Jackson 2014).

Types of Tannins

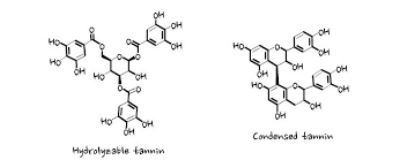

To be able to decipher the catalogue descriptions, it is helpful to review the types of tannins found in wine. Tannins in wine can come from grape skins, grape seed, and oak. Tannins from seeds and skin tend to be condensed tannins. Chemically, these are made up of catechin and epicatechin subunits that do not easily dissociate under acidic conditions. These provide the majority of bitter and astringent flavor of the wine and also complex with anthocyanins. Monomeric catechins contribute to bitter flavor. When these subunits polymerize, they contribute rough, grainy, puckery, dry, dusty, and silky textures. Seed tannins can also include gallic acid components while skin tannins have these less often. Condensed tannins are also sometimes called procyanidins (Jackson 2014).

Chemical structures of hydrolysable vs. condensed tannins

The other type of tannin to be aware of are the hydrolysable tannins. These come primarily from oak and are made up of subunits of ellagic and gallic acid and their esters, combined with glucose. Hydolyzable tannins make up 10% of the heartwood of oak trees and perform an antimicrobial function for the tree. In the acidic conditions of wine, these tannins are broken up into their component parts. The esters of ellagic acid may serve as copigments for anthocyanins, helping to stabilize color in the short term, allowing time for more permanent bonds to form with condensed tannins. They are also readily oxidized, which means they act as antioxidants in wine (Jackson 2014).

Tannin Products

As you consider using tannin additions in your cellaring plan this year, it is important choose the tannins that answer your particular question. Tannins may be added for antioxidant protection, for structure, or to mask off flavors or better integrate green character. Different tannins serve different purposes. The protocols included in this email are meant to help you find the tannin product that best fits your wine. Contact the product rep for further guidance. Also, consider how much time the product needs to integrate. Some products are meant for aging, some are meant for fine tuning prior to bottling. Determining your plan early gives you the largest range of options for intervention.

It is important to do bench trials prior to addition. Due to the lighter body of the 2018 wines, the lower rates of addition may be all you need. You may also find that a combination of products does a better job than one product alone. Several of the reps have expressed the willingness to send sample packs to customers to allow for trials to determine the right product and dosage. Take them up on this offer!

References

Jackson, R. S. (2014). Wine science: Principles and applications. London: Elsevier/Academic Press.

Peynaud, E. (1997) The Taste of Wine: The Art and Science of Wine Appreciation. Wine Appreciation Guild

Vidal, S., Francis, L., Noble, A., Kwiatkowski, M., Cheynier, V., & Waters, E. (2004). Taste and mouth-feel properties of different types of tannin-like polyphenolic compounds and anthocyanins in wine. Analitica Chimica Acta, 513, 57-65.

Zoecklein, B. (2005). Enological Tannins. Enology Notes, (103). Retrieved October 22, 2018.

Zoecklein, B. (2005). Phenols, Wine Quality and Reductive Strength. Enology Notes, (160). Retrieved October 22, 2018.