Exploring long lees aging in Albariño (2023)

Melanie Natoli

Cana Vineyards and Winery

Summary

This experiment explored the impact of extended lees aging on Albariño in an effort to build texture, weight, and aromatic complexity for a reserve-style wine. Fruit was harvested and fermented under standard cellar conditions, then wines were divided for either early bottling or aging on lees for 14 months. The chemistry of the finished wines was very similar between treatments, and there was no significant difference between the wines in a triangle test. Those who were able to tell the difference between the wines scored the early bottling wine as having greater fruit intensity and complexity with a longer finish than the lees aged wine.

Introduction

This experiment was inspired by the Granbazán Don Álvaro de Bazán, an Albariño from Galicia, Spain known for its weight, depth, and aging potential. Melanie Natoli, winemaker at Cana Vineyards, already produces a bright, crisp, fruit-forward Albariño that is well received by customers. To complement this style, she sought to create a reserve expression with greater texture and complexity. Granbazán produces a range of Albariño wines, including verde, oak-aged, skin-fermented, and sparkling versions, with Don Álvaro de Bazán representing their reserve offering. This wine is made from old vines grown on poor, sandy granite soils, cropped at low yields, and fermented after a short cold soak with extended lees contact. It is aged for 24 months on lees to build aromatic complexity, roundness, and longevity, and is reported to show TA of 7.6 g/L, pH of 3.31, 1.8 g/L residual sugar, and 13.9% ethanol1. While future trials at Cana may also investigate skin contact, this study focused specifically on the role of extended lees aging in shaping mouthfeel, complexity, and overall wine quality.

During lees aging, yeast cells undergo autolysis, an organized process of degradation after cell death2. Yeast autolysis is a very slow process at the pH and alcohol found in normal wine conditions3,4. It takes about two months post fermentation for the number of potentially fermenting cells to significantly decrease5. Autolysis doesn’t begin until 2-4 months after the end of fermentation (4-6 months after the beginning of fermentation)4,5, though amino acids located within the cells are passively released into the wine immediately after sugar exhaustion3. Some sources extend the beginning of autolysis to 3-9 months post fermentation, depending on the chemistry of the wine and yeast strain4. After 2-9 months, membrane bound structures within the yeast cell begin to break down. Destructive enzymes sequestered in these structures are released into the cytoplasm and begin to degrade cellular compunds3,4. Glucanases and proteases degrade the inner portion of the cell wall, releasing embedded mannoproteins. Though the cell wall remains intact, it become porous, allowing the products of autolysis to leak out3,4,6. Over time, yeast cells loose most of the contents of the cytoplasm, including the enzymes (proteases, glucanases, nucleases) that continue to degrade polymers even after release into the wine4. Nitrogen in wine increases significantly between 18 and 25 months of aging on lees due to continued breakdown of proteins7. Degradation of cell membranes may also lead to release of lipids4.

Several different classes of compounds are released by autolysis, each of which has an impact on wine chemical and sensory properties.

- Mannoproteins are highly glycosylated proteins that make up almost 50% of yeast cell walls. The concentration of mannoproteins varies based on yeast strain, must turbidity and growing conditions8. Mannoproteins are a major contributor to the mouthfeel of the wine, lending sweetness and lengthening the finish5,9. Interactions between mannoproteins and phenolics may reduce astringency or bitterness9. Chemically, they contribute to tartrate stability by capping growing tartrate crystals10. They may also reduce protein haze formation due to interactions with unknown factors that decrease particle size and reduce turbidity4. Polysaccharides such as mannan and B-glucan are released from mannoproteins. In barrel aged wines, the interaction of polysaccharides with oak tannins reduced the adsorption of fruity esters by oak cooperage2, also increasing the fruitiness of the wine. However, polysaccharides are eventually broken down into glucose and other sugars, which may fuel the growth of microbes.

- Amino acids released from cells and proteins during autolysis may provide precursors for new aroma compounds through deamination and decarboxylation reactions. These processes contribute to the “toasty” flavor associated with aging sparkling wine on lees5, and may increase overall wine complexity4. However, the release of amino acids also increases the pool of available of nitrogen that could support the growth of spoilage microbes9.

- Release of volatile compounds such as esters and terpenes leads to changes in fruity and floral aromatics4.

The main concerns for winemakers during long lees aging are unwanted malolactic fermentation, oxidation or reduction, and the activity of spoilage organisms. Aging in topped vessels with adequate levels of SO2 can prevent oxidation while also inhibiting malolactic fermentation and the production of acetic acid. The cell walls of yeast are a reductive surface, helping to scavenge oxygen introduced during barrel aging and stirring, but can themselves contribute to reductive odors if not managed carefully2,9. The risk of reduction is increased by pressure in larger vessels such as tanks or foudres2,9. The extent of reduction can be limited by including only light lees and leaving heavy lees behind11. Heavy lees are those that settle out in the first 24 hours and can contain unwanted materials such as pulp and tartrates while light lees are those still present in solution after 24 hours. The light lees contain living and dead cells and are the desirable portion for sur lie maturation. Weekly to monthly battonage is also recommended to prevent reduction. Stirring homogenizes the redox potential of the wine from the top of the vessel to the bottom, leading to less reduction at the bottom. Opening the bung of a barrel or the top of the tank to stir also introduces oxygen, which can limit reduction. (Care must be taken, however, as the introduction of oxygen can also lead to formation of acetaldehyde and potentially lead to acetic acid production9.) Stirring also helps break down the cell walls, releasing B-1,3-glucanase enzymes and mannoproteins9, and favors diffusion of nutrients, mannoproteins, and flavorants from yeasts into the wine2. Stirring distributes any spoilage organisms that may be present in the bottom of the barrel.

The purpose of this experiment was to compare wine chemical and sensory characteristics in an early bottled vs. long lees aged Albariño. Wine was fermented as one larger lot, then split into two lots for aging and bottling. One lot was racked to a storage tank for longer term aging shortly after the end of fermentation, to preserve dissolved CO2 and capture lees in suspension. The other portion was allowed to settle, racked off lees, and bottled early. Sensory analysis was completed 14 months after the early bottling and 4 months after the later bottling.

Methods

Albariño grapes were hand harvested, chilled overnight, then pressed with the addition of 30 ppm SO2, 25 mL/ton CinnFree (Scottlabs) and 30 g/hL Glutastar (Scottlabs). Juice was cold settled at 42°F for 48 hours before racking to a single large tank for fermentation. Prior to inoculation, 0.4 g/L tartaric acid was added to a target pH of 3.36 (based on an in-house acid trial). Fermentation was inoculated with 25 g/hL IOC BeFruits rehydrated in 30 g/hL Go Ferm Sterol Flash. Fermentation progressed at a temperature between 56°F and 60°F. Fermaid O was added twice, once at the beginning of Brix drop (20 g/hL) and again once the fermentation reached 14° Brix (10 g/hL). At 10° Brix, the tank was pumped over and splashed for 10 minutes, with the addition of FT Blanc Soft 10g/HL and OptiWhite 30g/HL.

At the completion of fermentation, once heavy lees had settled but before light lees had fully compacted, the wine was racked to two tanks under a protective blanket of CO₂. Each tank received an addition of 20 g/hL Pure-Lees Longevity Plus.

- The wine intended for long lees aging was racked to an 850L close topped tank (without glycol) with the addition of 100 ppm SO2. This tank was kept topped and sealed with infrequent stirring (a difficult task in a topped tank).

- The remaining wine was racked to another tank with the addition of 65 ppm. This wine was used for the early bottling.

Both wines were prepared for bottling with the addition of Granubent at a rate determined by bentonite trial, then cold stabilized at 30-32°F, racked and cross flow filtered. The early bottled wine was bottled in January of 2024 (after only a few months in tank) while the long-aged wine was bottled in January of 2025 (after 14 months of aging).

Sensory analysis was completed by a panel of 25 wine producers using shipped samples. Each wine producer received 3 wines in identical bottles, filled on the same day, each coded with random numbers. Of the three wines, two were identical and the participant was asked to identify which wine was different (a triangle test). There were four tasting groups with the unique wine in the triangle test balanced between groups. Tasters were then asked to score each wine on a scale of 0 to 10 for fruit intensity, fruit complexity, palate weight/volume, perception of acidity, and finish. Results for the triangle test were analyzed using a one-tailed Z test. Descriptive scores were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

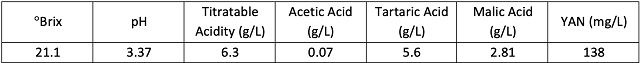

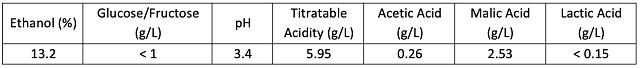

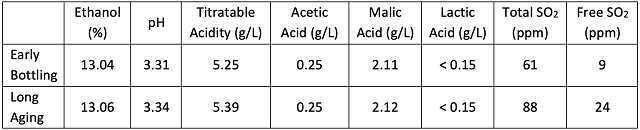

Fruit was clean and ripe at harvest (Table 1) and proceeded through a robust fermentation. At the completion of fermentation, the wine had low acetic acid and no detectable lactic acid, indicating the wine had not undergone malolactic fermentation (Table 2).

Table 1: Juice chemistry (Vinterra Lab, September 14, 2023)

Table 2: Post fermentation wine chemistry (ICV Labs, December 2023)

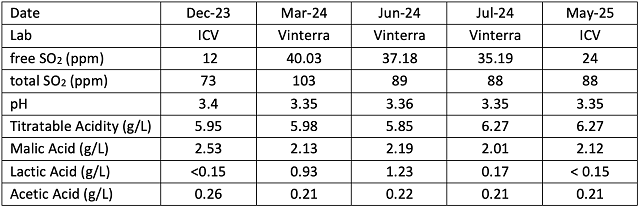

The winemaking goal for the long aging wine was to increase mouthfeel/palate weight while maintaining freshness and fruit character. One of the main concerns of long aging on lees was that the wine would change character due to malolactic fermentation. Malolactic fermentation is thought to be inhibited when total SO2 is greater than 50 ppm, so in theory, the 100 ppm addition at the end of fermentation should have been sufficient to prevent this conversion.

Chemical testing during aging indicated that there was some lactic acid present in the wine in March, and again in June (Table 3), however there was no increase in acetic acid or pH, and the wine did not have any sensory characteristics of malolactic fermentation when tasted by staff from Cana and the WRE. Subsequent tests did not register meaningful amounts of lactic acid, indicating that positive results for lactic acid in March and June may have been erroneous.

Table 3: Wine chemistry through extended aging (ICV Labs & Vinterra Winery Services)

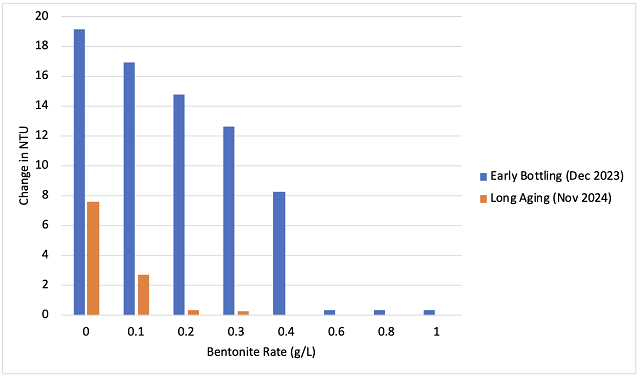

Another potential impact of extended lees aging is a reduction in protein instability, likely due to the interaction of wine proteins with mannoproteins released from yeast autolysis. A bentonite trial conducted by Imbibe Solutions one to two months prior to bottling demonstrated this effect: the early-bottled wine required nearly 0.6 g/L of Granubent to achieve protein stability, whereas the lees-aged wine required only 0.2 g/L (Figure 1). Post bottling testing confirmed these wines were protein stable (data not shown). There was no notable difference in wine chemistry in the bottled wine between treatments (Table 4). The early bottled wine had lower free SO2 at the time that sensory analysis was done, most likely due to the longer amount time bottle aging.

Figure 1: Pre-bottling bentonite trial (Imbibe Solutions). A change of 2 NTU or less indicates the wine is stable.

Table 4: Wine chemistry at the time of sensory analysis (ICV Labs, May 2025)

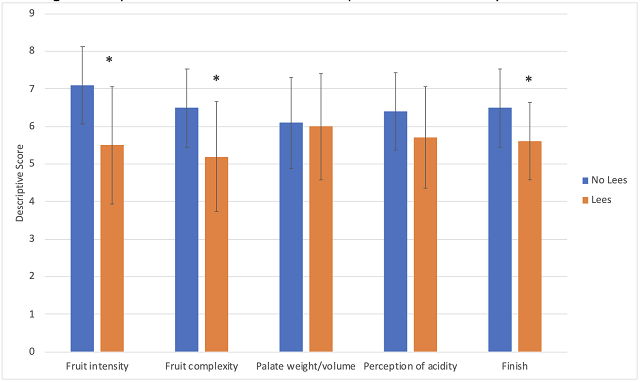

In a triangle test of Albariño that was bottled early or aged on lees, 11 out of 25 winemakers were able to distinguish which wine was different, indicating that the wines were not significantly different (Z=0.92, p=0.18). The early bottled wine scored significantly higher than the lees aged wine for fruit intensity, fruit complexity, and length of finish (p=0.01, p=0.00, p=0.02). There were no significant differences in scores for palate weight/volume and perception of acidity (Figure 2). Open ended responses indicated that some winemakers felt that the lees aged wine felt older and more tired than the wine without lees, both aromatically and on the palate.

Figure 2: Repeated measures ANOVA of descriptive scores for two styles of Albariño

References

(1) Granbazán don Alvaro de Bazán. Bodegas Granbazan. https://www.bodegasgranbazan.com/en/granbazan-d-alvaro-de-bazan/# (accessed 2025-05-21).

(2) Jackson, R. S. Wine Science: Principles and Applications, 4 edition.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2014.

(3) Dharmadhikari, M. Yeast Autolysis*. Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/wine/yeast-autolysis (accessed 2019-12-24).

(4) Alexandre, H.; Guilloux-Benatier, M. Yeast Autolysis in Sparkling Wine – a Review. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2006, 12 (2), 119–127.

(5) Moss, R. The Beauty of Self-Destruction – Yeast Autolysis in Sparkling Wine.

(6) Castor, J. G. B.; Vosti, D. C. Yeast Autolysis a Seminar. Am J Enol Vitic. 1950, 1 (1), 37–46.

(7) Leroy, M. J.; Charpentier, M.; Duteurtre, B.; Feuillat, M.; Charpentier, C. Yeast Autolysis During Champagne Aging. Am J Enol Vitic. 1990, 41 (1), 21–28.

(8) Guadalupe, Z.; Martínez, L.; Ayestarán, B. Yeast Mannoproteins in Red Winemaking: Effect on Polysaccharide, Polyphenolic, and Color Composition. Am J Enol Vitic. 2010, 61 (2), 191–200.

(9) Zoecklein, B. W. The Nature of Wine Lees. Enology Notes No. 162.

(10) Chauffour, E. Understanding Wine Mouthfeel: The Art of Winemaking.

(11) Zoecklein, B. Lees Management. Enology Notes 2004, 106.