Building Body with Yeast Lees and Autolysis Products

Joy Ting

November 2018

One of the most common tools in the winery for the addition of body during elevage is the use of yeast lees. During aging, yeast lees can add to the perception of body, fine out astringency, and protect wine from oxidation. Yeast lees can originate from the fermentation, be added from other fermentations, or be purchased from an enological company. If using yeast lees from fermentation, take care that the lees are clean and do not contain spoilage organisms.

Wine body comes in part from polysaccharides. Though grapes contain a fair amount of polysaccharides that are released during crushing, pressing and maceration, these form complex colloids during fermentation that mostly precipitate out when alcohol is present. This means the grape polysaccharide level in finished wine is generally low. As polysaccharides extract along the same curve as anthocyanins, in years where grapes are underripe, initial extraction of grape polysaccharides can be low as well. (Jackson 2014)

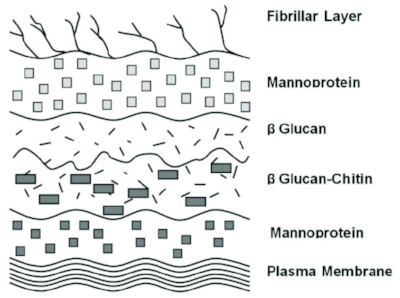

However, yeast also contribute polysaccharides to the wine. Mannans and B-glucans are the main carbohydrate formed by yeast as major portion of their cell walls. Most mannans are combined with proteins to form mannoproteins. These polysaccharides are released from yeast cell walls, some during fermentation and others during autoloysis after yeast cell death. Mannoproteins are further broken down to mannan (polysaccharide) and protein components. Generally, mannoproteins occur in the range of 150-200 mg/L in wine. (Jackson 2014, Dharmadhikari)

Figure 1 Architecture of a yest cell wall, from: https://www.researchgate.net/Schematic-diagram-of-the-architecture-yeast-cell-wall-Components-such-as-mannoprotein_fig7_324555072 [accessed 3 Nov, 2018]”

Sur lies maturation, the aging of wine on yeast cells, is employed fairly extensively worldwide. General practice includes 3-6 months of contact with lees with periodic stirring to favor diffusion of nutrients, mannoproteins, and flavorants from yeasts into the wine. During this time, dead and dying cells autolyze in a staged breakdown of the yeast . Over time, this process has been shown to release yeast metabolites (ethyl octanoate and ethyl decanoate) that add fruity character and contribute to enzymatic reduction that diminishes sensory impact of carbonyl compounds like diacetyl. Autolysis can also activate the release of aromatic compounds from precursors. In some cases, it has been shown to reduce the sensory defects of 4-EP’s. The liberation of manno-proteins from cell walls is thought to soften the taste of red wines by binding or precipitating oak and grape tannins and reducing the adsorption of fruity esters by oak cooperage. For all of these reasons, sur lies aging can shift the balance equation to the left, favoring sweetness and fruitiness while diminishing acidity and astringency. (Jackson 2014, Zoecklein. 2005)

Lees are chemically reductive, which can help protect against oxidation, but can also promote the formation of sulfur like off odors, so weekly to monthly battonage is usually recommended to prevent this. The threat of reduction is exacerbated by pressure in larger vessels, so take care if you are aging sur lies in tanks or foudres. In small cooperage, lees seem to metabolize or adsorb mercaptans. Depending on the strain of yeast used, lees can have significant release of glucose during autolysis, increasing risk of microbial spoilage, so proper cleaning is needed prior to filling barrels to prevent Brett growth. (Jackson 2014)

In Enology Notes #85, Zoecklein (2004) reports on a trial of dry yeast fining using 1 g/L of yeast post fermentation without hydration with weekly battonage for three weeks before racking. Chemical and sensory results are reported, showing a decrease in color coupled with softening of phenols and increase in body as well as a decrease in perception of herbaceous character and increase in berry fruit intensity. These results were variable, so fining trials should be done prior to cellar usage. Enology Notes #106 also provides a broader discussion of lees management as well as insight into aspects of battonage that should be considered. Enology Notes #108 also mentions that yeast fining is much more “forgiving” when used on younger vs. older red wines. So if you are considering a form of lees treatment, consider doing this sooner rather than later.

Sur Lies elevage can be done on lees from the primary fermentation or using added lees from other sources. Zoecklein (2005) makes the distinction between heavy lees, those that fall out in the first 24 hours and can contain unwanted materials such as pulp and tartrates, and the light lees, those that are still present in solution after 24 hours. The light lees are desirable for sur lie maturation. Some have used lees from finished white wine fermentations. Others have added dry yeast (Zoecklein 2004). Several commercial products are available to provide sources of yeast mannoproteins. Products recommended by company representatives are listed by their trade names can be found here (insert link to recommendation section – will be at end of learn module). Be aware that different products have different intended treatment times. In general, the slower release formulations are more likely to have an integrated result, and they tend to be less expensive. Some companies also offer enzymes that hasten autolysis, releasing mannoproteins and other cellular constituents more quickly.

Several WRE trials have been done using lees aging in white and red wines. Results for these trials can be found in the Learn module “Building Body and Structure in Red Wine” or by searching Additives/Lees and Mannoprotein products and Operaitons/Lees Management

References

Dharmadhikari, M. (n.d.). Yeast Autolysis. Iowa State Extension. Retrieved October 22, 2018, from https://www.extension.iastate.edu/wine/files/page/files/yeastautolysis1.pdf.

Jackson, R. S. (2014). Wine science: Principles and applications. London: Elsevier/Academic Press.

Zoecklein, B. (2004). Yeast Fining. Enology Notes, (85). Retrieved October 22, 2018.

Zoecklein, B. (2005). Lees management. Enology Notes, (106). Retrieved October 22, 2018.