Strategies for acid adjustment

Joy Ting

September 2020

Acid adjustment is a common occurrence in Virginia winemaking, and may be needed in some cases in 2020. If you find yourself in the situation where you need to add acid, here are a few things to keep in mind.

- Gather as much information as you can by measuring pH, TA, and doing an acid trial. It is best to do acid trials and run TA on samples just before inoculation, to account for any differences that have occurred during settling or cold soak. For white, this means after racking. At the juice stage, it is difficult to assess the sensory effects of acid additions, but if you are thinking of adding acid to finished wine, a taste trial is also a helpful tool. See above for protocols for each of these tests.

- There are no hard and fast rules for pH and TA limits1, but rather principles and ranges to keep in mind. It is possible you will need to compromise on one target or another. Keep the principles of wine acidity in mind as you make your choices.

- Fermentation changes things. It is likely pH will increase and TA will decrease during fermentation due to the effects of increasing ethanol, precipitation of bitartrate, utilization of malic acid by yeast, production of succinic acid, consumption of amino acids, and extent of malolactic fermentation2.

Acid addition

Timing: It is generally preferred to add acid earlier vs. later in order to maximize the benefits of microbial stability and to allow for better flavor integration. However, it is more difficult to know exactly what you will need pre-fermentation. Some winemakers prefer to add ¾ of the anticipated addition prior to fermentation and the remainder after fermentation, when sensory trials can be conducted and the effects of fermentation are fully known.2

Which acid to add: Tartaric acid is the most common acid used to adjust the pH of the wine. Unlike malic and citric acids, tartaric acid is relatively insensitive to microbial decomposition.2 Addition of tartaric acid will result in a greater change in pH than the same concentration of malic acid because tartaric is more highly ionized than malic at normal wine pH and is a “stronger” weak acid, meaning it can contribute protons more easily to lower the pH.1,3 One disadvantage of adding acid as tartaric is loss due to crystallization as potassium bitartrate. This is especially pronounced in juice and with high levels of potassium.1

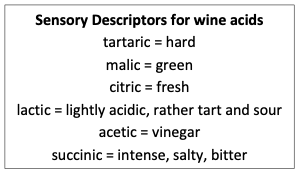

Some winemakers feel that large additions of tartaric acid shift the normal sensory profile of the wine and therefore prefer to add a blend of tartaric and malic acids.3 Wine acids have been described for their sensory character beyond mere acidity (sidebar).4

The true proportion of tartaric to malic acid in wine varies by cultivar and region2,5,6. The Sentinel Vineyard Project and WRE are tracking these metrics in several varieties in Virginia in 2020. One important note: do NOT add citric acid before fermentation. Citric acid can inhibit fermentative enzymes and can be metabolized by lactic acid bacteria to form acetic acid.3

Decreasing acidity

Malolactic Fermentation: It is generally thought that malic acid has a stronger perception of acidity than lactic acid, so one strategy to decrease sourness is to let the wine undergo malolactic conversion (or inoculate it with ML bacteria). This will also increase the pH of the wine, the extent of which depends on the buffer capacity of the specific wine, averaging 0.1 – 0.2 pH units per gram of malic acid converted.2 If you choose to inoculate with malic acid bacteria, keep in mind that these microbes also consume citric acid to produce diactyl. Choose a strain that fits the sensory impact you are looking for (high vs. low diacetyl). Also, keep in mind that lactic acid levels of 1.5 g/L will slow down malic acid bacteria and levels above 3 g/L may inhibit these bacteria.7

Cold Stabilization: During cold stabilization, potassium bitartrate precipitates from the wine solution resulting in as much as 2 g/L decrease in TA.3. The effect on pH depends on the initial pH of the wine. When tartrate is lost, the equilibrium of these three forms will shift. If the initial pH of the wine is greater than 3.65, the equilibrium will shift in a way that takes up a proton, which increases the pH. If the initial pH of the wine is less than 3.65, the shift in equilibrium will result in release of a proton, and decrease in pH.1–3 (Boulton points out that in an ethanol based solution, this break point may be closer to 4.1, good news for winemakers.2

The special case of high pH, high TA

The special case of high pH, high TA leads to some difficult decisions for winemakers. This situation is caused when high levels of potassium are traded off for protons by grapes (increasing the pH), leaving tartrate ions behind (still contributing to TA). It is common in cold climates when malic acid is elevated due to cool nights but potassium is present1 and has also been reported in Australia due to high potassium levels.5 When this is the case, knowing TA levels, malic acid levels, and doing acid trials becomes even more important. The AWRI recommends large acid additions as early as possible in fermentation in an attempt to precipitate out excess potassium. Ion exchange can also be used for this purpose5.

References

(1) Jackson, R. S. Wine Science: Principles and Applications, 4 edition.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2014.

(2) Boulton, R.; Singleton, V. L.; Bisson, L. F.; Kunkee, R. E. Principles and Practices in Winemaking; Chapman and Hall, Inc: New York, 1996.

(3) Zoecklein, B.; Fugelsang, K. C.; Gump, B. H.; Nury, F. S. Wine Analysis and Production; Springer: New York, 1995.

(4) Peynaud, E. The Taste of Wine: The Art and Science of Wine Appreciation; The Wine Appreciation Guild LTD: San Francisco, California, 1987.

(5) Ask the AWRI: Winemaking with High PH, High TA and High Potassium Fruit. Grapegrower and Winemaker 2018, October (657).

(6) Kliewer, W. M.; Howarth, L.; Omori, M. Concentrations of Tartaric Acid and Malic Acids and Their Salts in Vitis Vinifera Grapes. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 1967, 18, 42–54.

(7) Scottlabs. Fermentation Handbook; 2018.