The Effect of Enzyme, Cap Management, and Tannin on Phenolics in Merlot (2016)

Ben Jordan

Early Mountain Vineyards

Summary

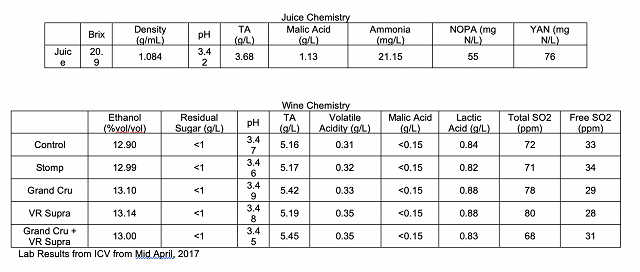

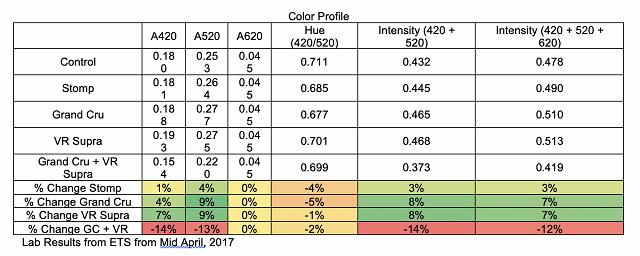

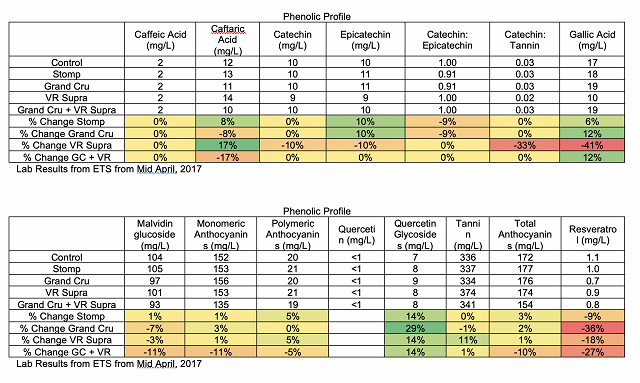

This study examined the impact of 5 winemaking techniques on the phenolic composition of Merlot. The treatments were as follows: 1) Control, 2) Stomping grapes during a delestage (otherwise identical to control), 3) Lafase Grand Cru (Laffort) at crush, 4) VR Supra (Laffort) at crush, and 5) Both Lafase Grand Cru and VR Supra at crush. All other treatments were the same between wines. All wines had a delestage operation performed at 2 Brix, where stomping occurred for the stomping treatment. There were no major chemical differences between wines. Stomping had very little effect on phenolic chemistry. VR Supra and Grand Cru alone increased color, but when combined color was lowered (corresponding to lower anthocyanins). No other impacts on phenolic qualities could be observed, except tannin was increased and gallic acid decreased in the wine treated with VR Supra. The sensory impact of the VR supra treatment cannot be adequately assessed due to it being an outlier. Overall, the treatments tended to slightly increase Fruit Intensity and Body relative to the Control. The stomped wine tended to be the most preferred wines for all but the May 3 Tasting. Grand Cru + VR Supra also tended to be regarded fairly highly. The Control wine tended to be the least preferred. These results were not very strong, however, and more studies on the impacts of these treatments on the chemical and sensory qualities of wine should be performed. Additionally, more work should be done to examine the impact of these treatments on wine during aging.

Introduction

Often oak chips, enological tannin, or even skins from other grapes are added to must prior to the onset of fermentation. It is thought that these additions may help prevent oxidation, enhance color stability, and enhance phenolic quality and mouthfeel. They may also ameliorate tannin problems from unripe or damaged fruit, increase the amount of tannin available to form polymeric pigment, and reduce vegetal aroma (Zoecklein 2005). Some authors have observed that exogenous tannin can both enhance the final concentration of anythocyanin in wine after 72 hours of fermentation (Giacosa et al. 2017). It is not clear from this study how stable this difference in wine is over time. These effects all depend on the source and kind of tannin (hydrolysable vs condensed tannin). All grape-derived tannin is condensed tannin, whereas hydrolysable tannin comes from oak wood or additives (Zoecklein 2005).

The timing of tannin addition will greatly impact the effect of these tannins, with earlier additions having less of an impact. Although pre-fermentation additions may help the exogenous tannin to integrate more fully with grape phenolics to form polymeric pigment, yeast cell walls will often bind tannin during precipitation, thus in effect “fining” tannin out of wine (Zoecklein 2000; Zoecklein 2005). Additionally, sometimes tannin addition can result in protein precipitation in must, causing a cascade of tannin precipitation which could actually result in lower tannin concentration in the finished wine (Steve Price, 2017, personal communication).

Some winemakers also will add pectolytic enzymes to aid in tannin and anthocyanin extraction. Pectinase and cellulase enzymes can help degrade grape cell walls, allowing for more release of vacuolar contents. This can increase cell wall tannin and vacuolar anthocyanin extraction, increasing red wine body (Zoecklein 2001). In general, pectolytic enzymes impact tannin more than anthocyanin, because tannin is less soluble. These enzymes can be very useful in short maceration times, such as if the winemaker is short-vatting. This aid in extraction may also help with phenolic polymerization in wines (Zoecklein 2006). This study examines the impact of exogenous tannin, pectolytic enzymes, and stomping on the chemical and sensory qualities of Merlot wine.

Results and Discussion

The maceration enzyme helped with pressing and clarification (not quantified), but testing to see if it helped with structure and color. There were no major chemical differences between wines. Stomping had very little effect on phenolic chemistry. VR Supra and Grand Cru alone increased color, but when combined color was lowered (corresponding to lower anthocyanins). No other impacts on phenolic qualities could be observed, except tannin was increased and gallic acid decreased in the wine treated with VR Supra.

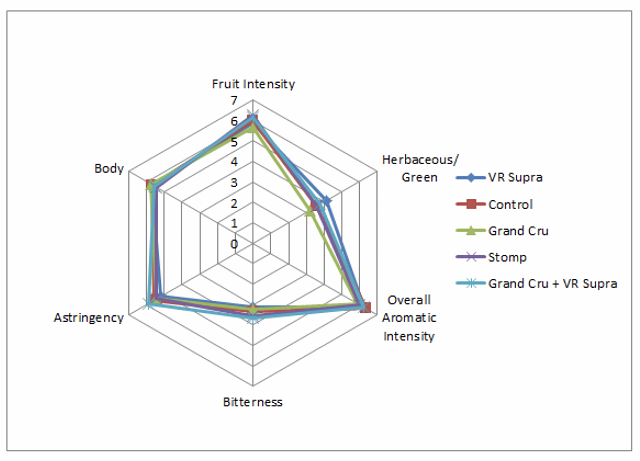

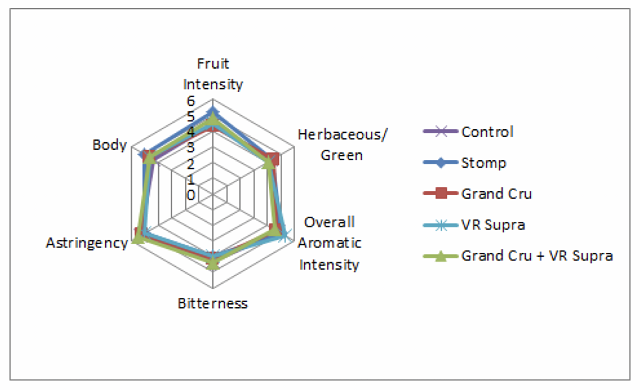

Descriptive analysis for the May 3 tasting did not show any strong trends with the descriptors used in this study. There were slight tendencies for the Grand Cru treatment to have the least Herbaceous/Green character, and for the Grand Cru+VR Supra treatment to have the highest Bitterness and Astringency. The VR Supra treatment had the highest Herbaceous/Green character, but panelists seemed to think that this wine was an outlier compared to the rest (it had different oak flavor qualities, despite all being aged in identical neutral oak barrels). In general judges preferred the VR Supra and the Grand Cru + VR Supra wines. However, preference trends are hard to determine with the low number of judges. The preference for VR Supra seems to be due to a different oak quality that this wine had over the other wines.

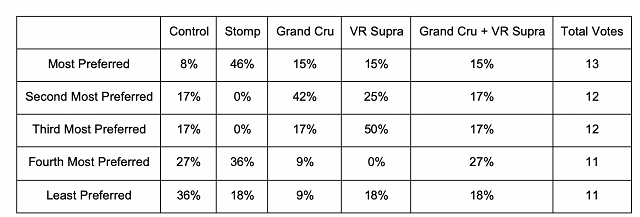

For the May 24 tasting, no strong trends could be seen with the descriptors used. There was a slight tendency for the stomped wine to have higher Fruit Intensity. The Control tended to have lower Body than the treatments as well. In general, the stomped wine was most preferred, followed by the Grand Cru wine. One judge had no preference.

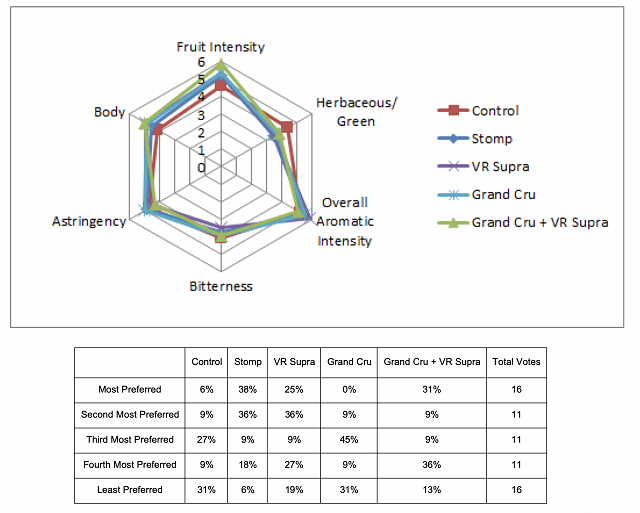

No strong trends could be seen with the descriptors used in this study on the May 31 tasting. There was a slight tendency for all of the treatments to increase Fruit Intensity and Body and lower Herbaceous/Green character relative to the control. The Grand Cru + VR Supra treatments tended to have the greatest impact on Fruit Intensity and Body. VR Supra also had a slight tendency to lower Bitterness. However, these trends were weak. In general, the Stomped wine and the wine with VR Supra were the most preferred, and the Control and Grand Cru wines were least preferred.

The impact of the VR supra treatment cannot be adequately assessed due to it being an outlier (it had different oak qualities than the other wines, despite being in an identical barrel). Overall, the treatments tended to slightly increase Fruit Intensity and Body relative to the Control. The stomped wine tended to be the most preferred wines for all but the May 3 Tasting. Grand Cru + VR Supra also tended to be regarded fairly highly. The Control wine tended to be the least preferred. These results were not very strong, however, and more studies on the impacts of these treatments on the chemical and sensory qualities of wine should be performed. Additionally, more work should be done to examine the impact of these treatments on wine during aging.

Methods

One block (3.068 tons) of Merlot grapes from Quaker Run Vineyard (5 West Upper Merlot) was harvested on 10/6 and was stored overnight. The lugs for this project were randomly selected when processing to help randomize the harvest Merlot harvested throughout the block. The following day the grapes were destemmed and sorted (not crushed) and were separated into 5 identical but separate fermentation T bins as follows:

- Control - nothing input

- Stomp - Use of stomp to crush during delestage only: otherwise like the control

- Grand Cru - use of Lafase Grand Crus Enzyme only at 40g/ton

- VR Supra - Use of VR Supra tannin only at 150g/ton

- Grand Cru and VR Supra - use of both enzyme and tannin at 40g/ton and 150g/ton

While processing, tannin and enzymes were layered in a way so that enzymes did not contact sulfur dioxide. Each wine received the same amount of sulfur dioxide. On 10/8, the bins were inoculated with Actiflore F33 at 0.15g/mL rehydrated with 0.2g/L Go Ferm Protect Evolution. On 10/13, 0.15g/L DAP and 0.2g/L Superfood was added, and on 10/15 5g/L sugar was added to the fermentations. There was 1 punchdown per day until fermentation started, at which point 3 punchdowns per day were initiated until the Brix dropped to 2. On 10/16 (at 2 Brix) delestage took place on each wine by racking all free run wine from the T bins and returning it back. At this point, the “Stomp” treatment was stomped in order to break as many of the skins as possible.

The bins underwent 5 days of extended maceration, and were then drained and pressed on 10/25, with the free run fraction being used for the remainder of the study. The wines were aged in identical neutral barrels. On 10/28 malolactic conversion was initiated with 0.002g/L Omega Enoferm. On 12/5 0.05g/L Stab Micro was added, along with 60ppm sulfur dioxide to stabilize the wines.

This project was tasted on May 3, May 24, and May 31. In order to balance the data set to perform statistical analysis for descriptive analysis on the May 3 tasting, any judge who had not fully completed the descriptive analysis ratings were removed. In order to then make the amount of judges between groups equivalent, one judge from group 1 and group 3 were eliminated. This resulted in a final data set of 3 groups, each with 3 judges (considered as replications within groups, and groups were considered as assessors). Data was analyzed using Panel Check V1.4.2. Because this is not a truly statistical set-up, any results which are found to be statistically significant (p<0.05) will be denoted as a “strong trend” or a “strong tendency,” as opposed to general trends or tendencies. The statistical significance here will ignore any other significant effects or interactions which may confound the results (such as a statistically significant interaction of Judge x Wine confounding a significant result from Wine alone). The descriptors used in this study were Fruit Intensity, Herbaceous/Green, Overall Aromatic Intensity, Bitterness, Astringency, and Body.

The same procedures for data analysis were used on the May 24 tasting. For the descriptive analysis in this tasting, in order to balance the data set one judge from group 3 was transferred to group 1, resulting in each group having 5 judges for a total of 15.

The same procedures for data analysis were used on the May 31 tasting. For the descriptive analysis in this tasting, one judge was eliminated from group two and three so that each group had four judges, for a total of 12 judges.

References

Giacosa, S., Segade, S.R., Rolle, L., and Gerbi, V. 2017. Study of the role of exogenous tannins in color preservation during the early stages of maceration. Universitá degli studi di torino.

Steve Price, Personal Communication, 2017.

Zoecklein, B. 2000. Wine structural development. Enology Noes #8. http://www.apps.fst.vt.edu/extension/enology/EN/8.html.

Zoecklein, B. 2001. Enhancing varietal aroma/flavor intensity. Enology Notes #29. http://www.apps.fst.vt.edu/extension/enology/EN/29.html.

Zoecklein, B. 2005. Enological tannins. Enology Notes #103. http://www.apps.fst.vt.edu/extension/enology/EN/103.html.

Zoecklein, B. 2006. Pectic enzymes. Enology Notes #117. http://www.apps.fst.vt.edu/extension/enology/EN/117.html.