Introduction to Cofermentation

Joy Ting

Co-fermentation of Petit Verdot and Petit Manseng at King family Vineyards. Photo Credit: Matthieu Finot

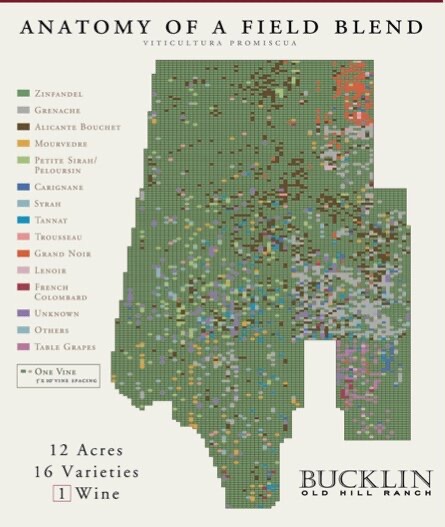

Simply stated, co-fermentation as “the simultaneous fermentation of two or more varieties in the same vessel”(1). This ancient technique likely arose from a time when vineyards were interplanted with several varieties, either due to the availability of replacement vines or simply the lack of techniques to determine varietal identity. Some well known wines have traditionally been produced as co-ferments including Côte Rôtie from the Northern Rhône which usually includes 5-10% Viognier added to Syrah. Chianti Classico was historically a co-ferment of Sangiovese with the indigenous red grape Canaiolo Nero as well Trebbiano and Malvasia, both white varieties. Interplanted vineyards can also be found in the New World. Bucklin’s Old Hill Ranch vineyard, one of the oldest in California, is an interplanting of 16 varieties on 12 acres, all harvested and vinified together(2). On a recent trip to California, my husband and I visited Ridge Vineyards, whose Geyserville “Old Patch” contains vines up to 130 years old that include Zinfandel interplanted with Carignane, Petit Syrah and Mourvedre. This vineyard is picked and vinified as a co-fermented field blend with stunning results.

Winemakers use co-fermentation for many reasons. Some cite a “lifting of the aromas”, “enhanced texture”, “softening of the wine” or “improved brilliance and intensity of color”(1,3), while others, like Bucklin and Ridge, honor their terroir and history. In many cases, increased color stability is cited as a reason for co-fermentation. It is counterintuitive to add a white wine to a red to stabilize color, Roger Boulton (2001)(4) provided a chemical explanation for this approach in his work on co-pigmentation. When anthocyanins, the main pigments in red wines, are extracted from grapes, they can take on five different chemical forms, only one of which has red color(3). Anthocyanins are also subject to loss of color through the bleaching effects of SO2 or by binding with other chemical constituents, including oxygen(3). The colored form of anthocyanins is more prevalent in lower pH wines, and can be stabilized by association with other anthocyanins or other phenolics in the wine. These other phenolics, referred to as co-pigments, form weakly bonded stacks of flat molecules, sandwiching the anthocyanins in a way that that protects them from bleaching, and may increase the likelihood of forming long-term bonds with tannins, further stabilizing color. Co-pigmented anthocyanins take on a slightly bluer form, leading to the purple tones found in young red wines. Boulton (2001) hypothesized that some varieties have more co-pigments than others, and, in red wines with poor color stability, color could be enhanced by addition of co-pigments)3,4).

from https://www.buckzin.com

When tested directly, though, co-fermentation has variable effect on color, as reviewed by Casassa et al (2012)(5). Gigliotti found increased color in one-year old Sangiovese wine co-fermented with Trebbiano and Malvasia. The same was not the case for co-fermentation of Tempranilo with Viura (a Spanish white variety) studied by Etaio et al. In a study of co-fermentation of Syrah with 5, 10, and 20% Viognier, Casassa et al (2012) found that addition of 10 and 20% Viognier led to wine with lower color measurements. Both Syrah and Viognier were measured to have the same amount of skin and seed tannins, and there were no differences in tannins in the finished wines(5). So it seems that co-fermentation may lead to color enhancement or color dilution, depending on the circumstances.

Co-fermentation of hybrid grapes with Vitis vinifera varieties is even more complicated. Hybrid grapes contain on average 1.8 times lower levels of tannin than vinifera grapes, as well as higher levels of protein in pulp cells and higher levels of pectin in skin cells(6). During fermentation, tannins bind to these proteins and pectins and are removed, leading to a 5-fold difference in tannin in the finished wine6. Norton et al (2017) studied co-fermentation of a high tannin, low protein Vinifera variety, Cabernet Sauvignon, with a low tannin, high protein hybrid variety, Marquette. They found that finished Cabernet Sauvignon wine had five times the tannin concentration of the finished Marquette wine, with three times less protein. When co-fermentations included a high proportion of Marquette, tannin concentrations were significantly lower than calculated due to dilution alone, indicating that protein and tannin are binding during fermentation and reducing the overall tannin concentration. Based on this result, they suggest blending post-fermentation may be a better approach for tannin enhancement of hybrids(7).

So in the end, it is difficult to predict the outcome of co-fermentation. The best approach is to try it on a pilot scale and carefully observe the results. When considering co-fermentation in your own winery, there are a few practical considerations to keep in mind:

- Co-fermentation can include addition of whole fruit or addition of pressed skins.

- Varieties to be co-fermented must be ripe at the same time.

- If pressed skins need to be held for any period of time, adequate refrigeration, SO2, chitosan, and/or non-Saccharomyces yeast call be useful tools to prevent oxidation and microbial spoilage.

References

(1) Robinson, J. The Oxford Companion to Wine, 3rd Edition.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2006.

(2) Bucklin, W. Vineyard Map. Bucklin Old Hill Ranch.

(3) Jackson, R. S. Wine Science: Principles and Applications, 4th Edition.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2014.

(4) Boulton, R. The Copigmentation of Anthocyanins and Its Role in the Color of Red Wine: A Critical Review. Am J Enol Vitic. 2001, 52 (2), 67–87.

(5) Casassa, L. F.; Keirsey, L. S.; Mireles, M. S.; Harbertson, J. F. Cofermentation of Syrah with Viognier: Evolution of Color and Phenolics during Winemaking and Bottle Aging. Am J Enol Vitic. 2012, 63 (4), 538–543.

(6) Springer, L. F.; Sacks, G. Protein-Precipitable Tannin in Wines from Vitis Vinifera and Interspecific Hybrid Grapes (Vitis Sp.): Differences in Concentration, Extract- Ability, and Cell Wall Binding. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 62, 7515–7523.

(7) Norton, E. L.; Sacks, G. L.; Talbert, J. N. Nonlinear Behavior of Protein and Tannin in Wine Produced by Cofermentation of an Interspecific Hybrid (Vitis Spp.) and Vinifera Cultivar. Am J Enol Vitic. 2020, 71 (1), 26–32.