Granular Oak Additions to Cabernet Franc Must (2016)

Michael Heny

Horton Vineyards

Summary

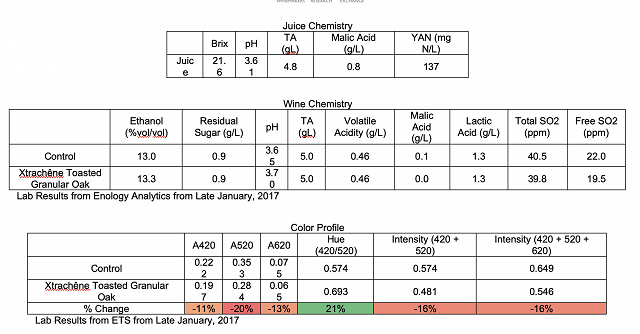

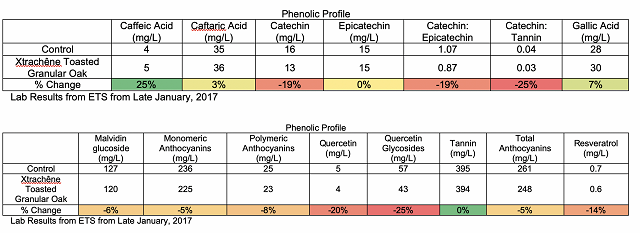

This study examined the effects of adding Xtrachêne Medium Toasted French granular oak to must at crush on the sensory and phenolic qualities of Cabernet Franc. Cabernet Franc was harvested from the same block, processed on the same day but kept separate, and one lot received 4 pounds per ton Xtrachêne Medium Toasted French granular oak whereas the other remained as a control. All other treatments between lots were the same. Wines made with granular oak exhibited greater hue and less color intensity. This shift in intensity may be due to the lowered levels of quercetin and anthocyanins in the wine produced with granular oak. Overall, there appeared to be a weak, but significant difference, between wines. No major preference trends could be seen, except for perhaps a weak preference for the control. No strong trends could be seen with descriptive analysis, except that on the second tasting most flavor attributes were lowered by the granular oak treatment. Due to the prevalence of this practice in Virginia, and the inconclusiveness of the results, more work should be performed on the impact of granular oak on wines.

Introduction

Oak adjuncts are often marketed to add volume to the palate, reduce vegetal characters, increase fruit character, and help with anthocyanin stability (Mitham 2010; Xtrachêne 2015; StaVin Inc.). Although they can impart oak aromas, not all kinds of oak adjuncts are marketed to have this impact. Untoasted oak, for example, may contain more hydrolysable tannins while imparting less oak aroma to wines. Additionally, the extractability of oak is measured in great part by the surface area of the adjunct, with granular oak having the highest level of extractability (Xtrachêne 2015; StaVin Inc.).

Although some have found that wine aged with oak chips tends to result in quicker development of polymerized tannin and overall aging factors than wine aged in barrels (del Alamo Sanza et al. 2004), others have found that the effects of adding oak chips to must do not result in consistent organoleptic and phenolic qualities, and are often indistinguishable from control wines (Zimman et al. 2002; García-Carpintero et al. 2011). In one study, oak chips during fermentation had no discernable effect, and varied depending on the site and fermentation. Some fermentations showed decreases in color and polymeric pigment, but others showed increases. In general, free anthocyanins decreased from the use of oak chips, possibly due to adsorption onto the oak chips (Zimman et al. 2002). This study had poor replications and variable control, however. In another study, oak chips reduced the extraction of total phenols during fermentation, although phenolic composition did not differ greatly between treatments (Zimman et al. 1999).

Ellagic acid and other oak constituents may act as antioxidants, protecting other phenolic compounds from degrading (Vivas and Glories 1996; Puech et al. 1999). It does not appear that polymeric, stable pigment derived from oak tannins are formed; however, the study in question was performed on model wine and the necessary precursors were just not available for the formation of polymeric pigment (Jordão et al. 2006). This antioxidant effect of ellagic acid could be an indirect mechanism for the formation of stable polymeric pigment from oak extracts. Indeed, one study found that ellagic tannins speed up the condensation of procyanidins and reduce the degradation of condensed tannins and anthocyanins (Vivas and Glories 1996) (this reduction of tannin degradation is contrary to the findings of Jordão et al. 2006). Ellagic tannins are more oxidizable than some wine phenolic compounds such as catechin, due to more hydroxyl groups in ortho positions per mole. However, these ellagitannins are also stronger oxidants, which result in more peroxide production and thus more aldehyde production. This may improve the formation of polymeric pigment during wine aging through acetaldehyde bridging. However, solutions with both catechin and ellagitannins produce less peroxides and consume oxygen slower than solutions with these compounds on their own. The authors suggest this rapid consumption of oxygen, followed by a large inhibition in consumption, is due to competitive inhibition of catechin with ellagitannins (Vivas and Glories 1996). This explanation needs further study: there must be some way in which the two compounds together inhibit iron cycling. The authors also suggested that ellagic tannins may act as antioxidants to protect catechin. Regardless, in this study ellagic tannins increased color intensity, helped form polymeric pigment, and led to decreased browning compared to oxidizing a control wine (Vivas and Glories 1996).

The effects of oak tannin on color stability in wine from true oak is also questionable. Condensed tannins are present only in low levels in oak heartwood, and are not likely to contribute much to wine, because wine has high levels of these naturally from grapes and the contribution from oak would be minimal (Puech et al. 1999). Condensed tannins (flavan-3-ols) are the phenolic compounds that are most responsible for forming polymeric pigment in wine. Ellagitannins are hydrolysable tannins, and it is unclear from a mechanistic sense how they would polymerize with anthocyanins. Furthermore, ellagitannins are only found in very low levels in oak-aged wines, despite being highly soluble. Toasting wood reduces the levels of ellagitannins at the toasting layer, resulting in less available to be extracted. Additionally, wines extract much less ellagitannins from wood than would be expected theoretically. Ellagitannins may also interact with polysaccharides and yeast proteins and mannoproteins, and as a result may be fined out of wine with yeast lees. Polymerization products are generally not from ellagitannins, and instead of polymerizing with anthocyanins and phenolics they appear to react with ethanol to form hemiketal derivatives. This also seems to occur instead of their reacting with oxygen and scavenging radicals, suggesting that their antioxidant effect may not be as pronounced as was previously thought (Puech et al. 1999).

Although winemakers use oak in part to stabilize color, it appears that the main benefit in oak adjunct use in winemaking is to mask or adsorb unwanted aromatics in wine, such as vegetal aromas. It is unlikely that much stabilization occurs from oak chips, due to the low concentrations of hydrolysable tannin that is added and because furfural, an oak compound that can condense with anthocyanins, is extracted at low concentrations as well. Additionally, some mouthfeel effects from oak also seem possible (Mitham 2010). However, added color stability is possible, but consistency in these results seems to be lacking. Oak adjuncts, in general, are very inconsistent in their results. This study examines the impact of different sources and kinds of oak added during crush on the chemical and sensory properties of wine.

Results and Discussion

Wines made with granular oak exhibited greater hue and less color intensity. This shift in intensity may be due to the lowered levels of quercetin and anthocyanins in the wine produced with granular oak. These results, however, were not very strong.

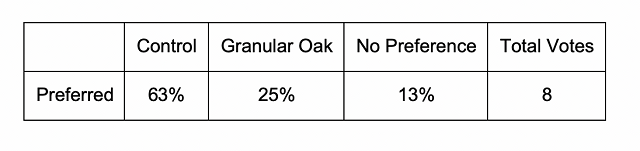

For the triangle test on May 24, of 11 people who answered, 4 people chose the correct wine (36%), suggesting that the wines were not significantly different. No preference trends could be seen for those judges who answered correctly. No strong trends were found for the descriptors used in this study. There was a slight tendency for the granular oak to increase Astringency.

For the triangle test on May 31, of 13 people who answered, 8 people chose the correct wine (62%), showing a statistically significant difference between wines (p<0.05). These wines were voted to have an average degree difference of 5.3 (out of 10), suggesting that the wines were moderately different. In general, people who answered correctly preferred the control treatment the most, although this was a weak preference. No strong trends could be seen with the descriptors used in this study. There was a slight tendency for the control to have higher Fruit Intensity, Body, Astringency, and Bitterness than the Granular Oak treatments. Several judges described these wines as being reductive, with the granular oak wines perhaps being slightly more reductive. This may have impacted the descriptive analysis.

Overall, there appeared to be a weak, but significant difference, between wines. No major preference trends could be seen, except for perhaps a weak preference for the control. No strong trends could be seen with descriptive analysis, except that on the second tasting most flavor attributes were lowered by the granular oak treatment. Due to the prevalence of this practice in Virginia, and the inconclusiveness of the results, more work should be performed on the impact of granular oak on wines.

Methods

Identically sourced Cabernet Franc grapes from Berry Hill Vineyard (Low Density Open Lyre Planting, 540 vines/acre, 3-4 year old vines with 214-3 year old vines on 3309C rootstocks and 326 4-year old vines on Riparia rootstock) were harvested on 9/26/2016. 11.7 tons were processed (4 tons per acre), were destemmed and crushed into 11-1 ton fermentation bins. The must was then treated with 60mLs/ton Color Pro, 30ppm sulfur dioxide, and then was inoculated with 20g/hL FX10. Some of these bins were separated into control and treatment bins, with 4 lbs/ton Medium toast granular French oak added to the treatment bin. Bins were punched down twice per day until the cap was submerged. On 9/28, 1g/L tartaric acid was added, and on 9/30, 20g/L sugar and 1g/hL MBR31 bacteria was added. At dryness (10/5), the control and treatment lots were pressed separately into separate containers. Following pressing, the wine received 2 aerative rackings (10/6 and 10/7) off of heavy lees before barreling into a mix of 2-5 year old neutral French and American oak. The wines were stirred and topped once per month. All samplings were taken from equal blends of wines from the oak.

This project was tasted on May 24 and May 31. For the triangle test and preference analysis, anybody who did not answer the form were removed from consideration for both triangle, degree of difference, and preference. Additionally, anybody who answered the triangle test incorrectly were removed from consideration for degree of difference and preference. Additionally, any data points for preference which did not make sense (such as a person ranking a wine and its replicate at most and least preferred, when they correctly guessed the odd wine) were removed.

In order to balance the data set to perform statistical analysis for descriptive analysis on the May 24 tasting, any judge who had not fully completed the descriptive analysis ratings were removed. In order to then make the number of judges between groups equivalent, one judge from group 3 was transferred to group 1, and another judge from group 3 was eliminated. This resulted in a final data set of 3 groups, each with 4 judges (considered as replications within groups, and groups were considered as assessors). Data was analyzed using Panel Check V1.4.2. Because this is not a truly statistical set-up, any results which are found to be statistically significant (p<0.05) will be denoted as a “strong trend” or a “strong tendency,” as opposed to general trends or tendencies. The statistical significance here will ignore any other significant effects or interactions which may confound the results (such as a statistically significant interaction of Judge x Wine confounding a significant result from Wine alone). The descriptors used in this study were Fruit Intensity, Herbaceous/Green, Overall Aromatic Intensity, Bitterness, Astringency, and Body.

The same procedures for data analysis were used on the May 31 tasting. For the descriptive analysis in this tasting, one judge was transferred from group three to group 2 so that each group had four judges, for a total of 12 judges.

References

del Alamo Sanza, M., Domínguez, I.N., Cárcel, L.M.C., and Gracia, L.N. 2004. Analysis for low molecular weight phenolic compounds in a red wine aged in oak chips. Analytica Chimica Acta. 513:229-237.

García-Carpintero, E.G., Gallego, M.A.G., Sánchez-Palomo, E., and González-Viñas, M.A. 2011. Sensory descriptive analysis of Bobal red wines treated with oak chips at different stages of winemaking. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 17: 368-377.

Jordão, A.M., Ricardo-da-Silva, J.M., and Laureano, O. 2006. Effect of oak constituents and oxygen on the evolution of malvidin-3-glucoside and (+)-catechin in model wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 57:377-381.

Mitham, P. 2010. Oak adjuncts in red ferments. How winemakers add oak early to improve aroma and texture. Wines and Vines. September. https://www.winesandvines.com/template.cfm?section=features&content=78082 Accessed 2/7/2017.

Puech, J.-L., Feuillat, F., and Mosedale, J.R. 1999. The tannins of oak heartwood: structure, properties, and their influence on wine flavor. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 50:469-478.

StaVin Inc. Fermentation Oak Chips and Granular. http://www.stavin.com/tank-systems/fermentation-oak-chips-and-granular. Accessed 2/7/2017.

Vivas, N. and Glories, Y. 1996. Role of oak wood ellagitannins in the oxidation process of red wines during aging. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 47:103-107.

Xtrachêne. 2015. Catalogue. http://www.xtrachene.fr/images/actualites/XC-Catalogue-EN.pdf. Accessed 2/8/2017.

Zimman, A., Fennedy, J.A., Joslin, W., Lyon, M.L., Meier, J., and Waterhouse, A.L. 1999. Phenolic extraction in commercial scale maceration trials II. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 50:364-384. Abstracts and Reviews.

Zimman, A., Joslin, W.S., Lyon, M.L., Meier, J., and Waterhouse, A.L. 2002. Maceration variables affecting phenolic composition in commercial-scale Cabernet Sauvignon winemaking trials. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 53:93-98.