The Winemaker’s Lab Manual

Protocols and Best Practices

November 3, 2025

How to measure free SO2

Joy Ting

January 2022

Free SO2 testing is likely the most common laboratory test performed in wineries regardless of size, with addition rates determined based on the result. In a 2019 survey of winemakers attending a WRE seminar on SO2 management, most Virginia wineries (90% of respondents) are measuring SO2 in-house using aeration oxidation (50%), Ripper titration (30%), or autotitration (20%), which is a modification of the Ripper method. Unfortunately free SO2 tests do not come with standard solutions because we cannot fix SO2 in the free form, eventually it will bind up and no longer be free. So how reliable are our results? Which of the available methods is best, and can a winemaker be sure he/she is working with a reliable number? In this newsletter we will examine the different methods for measuring free SO2 in a small to medium sized winery, discuss quality control measures and pros and cons of each approach. Specific protocols may differ among wineries, but these basic principles will apply broadly. For specific protocols to use in your own winery, we recommend those found in “Chemical Analysis of Grapes and Wine” (Iland et al 2004) and Wine Analysis and Production (Zoecklein et al 1995), though several textbooks and lab manuals will contain good examples.

Regardless of which method you use, it is important to use the appropriate measurement device. Any lab method has a limit to how robust it is to changes to the procedure1. Some steps require very careful measurement while others do not. If the protocol calls for dilution with a volumetric flask, this tells you that there is little room for error in this step. Volumetric pipettes are more accurate than transfer pipettes, and transfer pipettes are far better than graduated cylinders. It is worth the limited expense to purchase the appropriate measurement device in order to ensure a more accurate and precise result.

Ripper Titration

The Ripper method relies on a redox reaction between sulfur dioxide and iodine. The wine is first acidulated with sulfuric acid to reduce cross reaction of iodine with wine polyphenols2. Starch is added as an indicator that will turn color when it complexes with iodine. When Iodine is initially titrated into the wine/acid/starch mixture, sulfur dioxide from the wine reacts with iodine before it can complex with the starch, so there is no color change. When all of the sulfur dioxide has been complexed with iodine, excess iodine reacts with the starch to form an inky black end product, indicating the end to the titration. Based on the volume of iodine used, the amount of sulfur dioxide can be calculated with a simple conversion factor based on the concentration of iodine2–4.

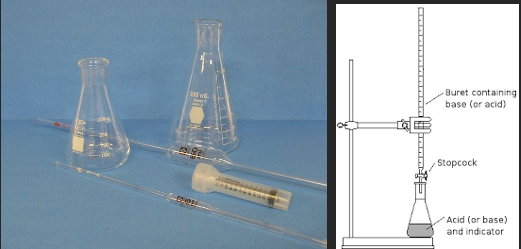

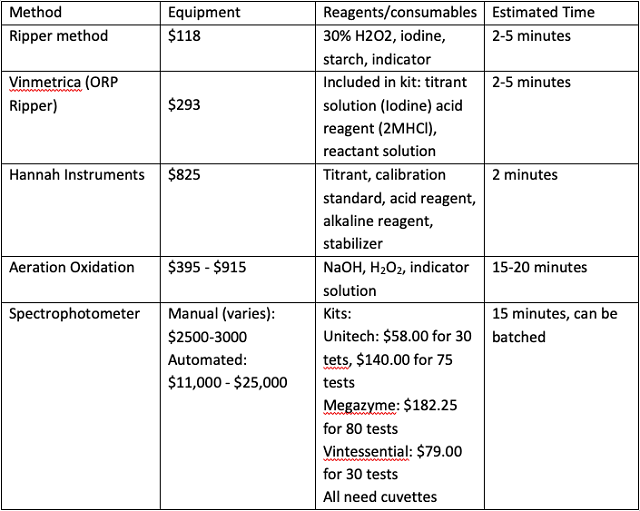

There are several elements to the Ripper titration that make it attractive for the small to medium sized winery. The entire procedure if very fast, it requires very little equipment (a burette, a flask, a pipette and a desk light, Figure 1), and it is very inexpensive (Table 1). However, there are several known inaccuracies with this approach. Once acidulated, SO2 is volatile and can be lost from the liquid/air interface during swirling4. Determination of the endpoint by a color change can be difficult in deeply colored red wines. Most importantly, there are other compounds in the wine matrix that also bind to iodine, most notably phenols, sugars, aldehydes, and ascorbic acid. This leads to an overall overestimation of SO2 present2,3.

If you are using the Ripper titration, there are some steps to take to make it as accurate as possible. A pinch of bicarbonate can be added to blanket the liquid/air interface with CO2, making volatilization of SO2 and dissolution of O2 less likely2,3. A small desk lamp can be used to provide backlight to the titration, making endpoint determination easier. Due to the instability of iodine, the concentration of this solution should be checked weekly, or potassium iodate could be used in its place to create iodine in situ5.

General QC recommendations also include

- Store iodine in a dark cabinet in dark glass bottle since it is light sensitive or the refrigerator to avoid microbial contamination2.

- Standardize the iodine solution as it will degrade over time (with an estimated shelf life of 3 months when stored properly). Iland et al 2004 has a good protocol for this.

- Though some kits supply a syringe for titration of iodine, it is better to use a microburette with a narrow bore opening to fine tune the titration.

- The endpoint is reached when the color changes to a dark blue and persists for 30 seconds.

- Work quickly (within 2 minutes) to avoid volatilization of SO2 at low pH and dissociation of SO2 bound to anthocyanins2,5

ORP detection methods

Several manufacturers, including Vinmetrica and Hanna Instruments, have developed oxidation/reduction sensing probes that detect a change in the current of the wine in the presence of excess iondine6. Sensing redox potential as opposed to a color change allows a better determination of the reaction endpoint in darkly colored wines2. The Hanna Instruments autotitrator also reduces human error by automating the titration step. However, since these methods still rely on the Ripper method, they are still subject to interferences from other wine components and iodine should be used promptly or standardized.

Aeration Oxidation

The aeration oxidation method seeks to avoid interferences by other components of the wine matrix by separating SO2 from the wine prior to measurement. During AO, acid is added to wine which is then subjected to either negative pressure (vacuum) or positive pressure (bubbling air) that separates molecular SO2 from the liquid. This gaseous SO2 passes through tubing to a second receptacle where it is trapped by a hydrogen peroxide solution, forming sulfuric acid. Because the wine is initially acidulated, most of the SO2 is in the molecular form and therefore measurable. After a measured amount of time (dependent on flow rate), the amount of sulfuric acid in the peroxide trap is determined by titration with NaOH. Though this methodology still relies on a color change to determine the end of titration, the peroxide solution is clear and therefore the endpoint is easier to read than in the Ripper titration2,3. However, several other difficulties remain

Aeration oxidation requires a more elaborate setup than the Ripper titration (Figure 1) with higher initial cost and longer reaction time (15 minutes per test). It still relies on a trained technician to accurately determine the endpoint, and care must be taken to keep solutions up to date. Because this method relies on separation by air movement, the flow rate of air through the wine must be calibrated, and the reaction must be carefully timed as too much or too little will affect the resulting value. When setting up the reaction, all tubing must be secure as any leaks will cause SO2 to escape, leading to aberrantly low values2–4.

General QC recommendations also include:

- Standardize NaOH often. Some recommend daily3, some say weekly4. Iland et al (204) recommend purchasing 0.1 M NaOH, which is more stable, and diluting to 0.01 N NaOH as needed, however this dilution must be done volumetrically to avoid error. NaOH can also be made from dry pellets at less cost and then standardized2–4.

- Hydrogen peroxide also degrades quickly in air, so a stock solution of 30% peroxide should be purchased from a trusted chemical supplier and stored in a dark bottle away from sunlight. A working solution of 0.3% should be made up at the time of use2,3.

- Store NaOH and Hydrogen peroxide in the refrigerator to slow degradation, but make sure working solutions are used at room temperature3.

- All testing should occur at cellar temperature3.

- Do not use NaOH that has been sitting in the burette overnight or for several hours. Good practice is to drain the burette at the end of each testing session. When refilling, make sure to flush any remaining solution completely, refill, and make sure to remove any air bubbles before titrating.

- The endpoint is reached when the magenta solution shows the first appearance of olive green. If you get to bright green, you have gone too far3.

- The flow rate of air should be 1L/minute.

Spectrophotometer based methods

In recent years, a third category of free SO2 determination has become available to the medium sized winery. This methodology relies on a quantitative reaction of bisulfite in the wine with fucsin and formaldehyde to produce a colored compound that can be measured with a spectrophotometer*5,7. A standard curve is built using standard solutions allowing for calibration within the protocol. Many medium sized wineries use spectrophotometers for measurement of volatile acidity, malic acid, residual sugar and juice nutrients, so this methodology adds one more function to this instrument. The reaction itself has been condensed into kit form by several manufacturers (Unitech, Vinessential, Megazyme and others) and can be run with an automated protocol on instruments such as the Chemwell. Several QC protocols are included in the kit procedure including sample blanking to avoid absorbance by polyphenols and pigments and use of a second reading to determine true SO2 vs. other oxidizable compounds that have reacted with reagents.

This methodology has been shown in internal documentation to be within 7ppm of traditional measures (Ripper and AO), with average differences of 1.5ppm for Chardonnay and 5ppm for red wines, with lower variation than either traditional metod5. However, this study was done on an automated spectrophotometer, which comes at considerable cost ($11,000-25,000 at the time of this writing). Package inserts from Megazyme and Vintessential also taut close correlation (r2=0.999) with results from AO measures of the same wine, leading to average differences of 1 mg/L (SD 4 mg/L). These kits can be used with a manual spectrophotometer, allowing several reactions to be processed in one run (decreasing time per test), however, manual operation includes the need for a trained technician as well as introducing potential error from pipetting, timing, cuvette cleanliness, etc… In a review of laboratory proficiency over 13 years and over 70 laboratories, Howe et al (2015) found spec based methods for free SO2 determination had very high values for variation. These authors hypothesize high values are due to a combination of factors including poor calibration of the spectrophotometer, pipette calibration, inappropriate cell path length, and dilution errors.

*The Vintessential kit relies on a different reaction than the Unitech and Megazyme kits. This approach includes acidification of the sample, leading to issues of bisulfite dissociation that will be discussed in the “Headspace” portion of this newsletter. Other aspects of the protocol (potential for automation, pipetting error, etc…) will apply to this kit.

Other methodologies

Several other methodologies for detection of sulfur dioxide in wine have been investigated8–11, however, most are either not yet ready for the production laboratory or they require expensive instrumentation and skilled operators that place them out of reach for small to medium sized wineries. These approaches are exciting developments and will be reported on as they become accessible for Virginia winemakers.

Figure 1: Comparative glassware needs and setup for the Ripper titration and Aeration Oxidation testing ($395) (www.carolinawinesupply.com)(gillypad.weebly.com)

Table 1: Comparative cost of materials and supplies for various methods of SO2 determination

References

(1) Butzke, C. E.; Ebeler, S. E. Survey of Analytical Methods and Winery Laboratory Proficiency. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 1999, 50 (4), 461–465.

(2) Zoecklein, D. B. Sulfur Dioxide (SO2). Enology Notes Downloads, 16.

(3) Iland, P.; Bruer, N.; Edwards, G.; Weeks, S.; Wilkes, E. Chemical Analysis of Grapes and Wine; Patrick Iland Wine Promotions PTY LTD: Campbelltown, Australia, 2004.

(4) Buechsenstein, J. W.; Ough, C. S. SO2 Determination by Aeration-Oxidation: A Comparison with Ripper. 1978, 29 (3), 4.

(5) Anderson, G. Free & Total Sulfur Dioxide Measurement. 9.

(6) Vinmetrica SC-100A User Manual Version 3.1c. Vinmetrica.

(7) Megazyme Free Sulfite Assay Procedure Manual. Megazyme 2017.

(8) Luque de Castro, M. D.; González-Rodríguez, J.; Pérez-Juan, P. Analytical Methods in Wineries: Is It Time to Change? Food Reviews International 2005, 21 (2), 231–265.

(9) Monro, T. M.; Moore, R. L.; Nguyen, M.-C.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Skouroumounis, G. K.; Elsey, G. M.; Taylor, D. K. Sensing Free Sulfur Dioxide in Wine. Sensors 2012, 12 (8), 10759–10773.

(10) Coelho, J. M.; Howe, P. A.; Sacks, G. L. A Headspace Gas Detection Tube Method to Measure SO2 in Wine without Disrupting SO2 Equilibria. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2015, 66 (3), 257–265.

(11) Jenkins, T. W.; Howe, P. A.; Sacks, G. L.; Waterhouse, A. L. Determination of Molecular and “Truly” Free Sulfur Dioxide in Wine: A Comparison of Headspace and Conventional Methods. Am J Enol Vitic. 2020, 71 (3), 222–230.

Recommended Protocol for Heat Stability Testing and Bentonite Trials

Winemakers Research Exchange

December 2019

This protocol for a fast heat test measures the change in turbidity after heating as an indicator of protein stability. Bentonite trials are run concurrently with a non-treated control to determine the dose of bentonite needed to achieve protein stability.

Make a 5% stock solution of pre-hydrated bentonite

The bentonite used for the trial should be from the same manufacturer, brand, and batch as the bentonite that will be used in the wine. Make up a new stock solution in the event a new bag of bentonite is opened.

- To make a 5% Bentonite stock solution(50g/L)(1:20 dilution), weigh out the mass of bentonite you will need. For 1 L of stock solution, you will need 50 g of bentonite.

- Measure 80% of the volume of water needed into a beaker with a stir bar. If you are making 1L of stock, you will need 800 mL or water, here. Use the same water as will be used in the winery to rehydrate bentonite for addition to wine. Adjust the stir plate to a moderate speed and slowly add the bentonite to avoid clumping.

- If a stir plate is not available, bentonite can be mixed in a close-topped container by inverting the container several times. It may take time to suspend all of the bentonite. Check carefully for any clumps that may remain.

- Heat can be used to encourage the bentonite to dissolve. Some bentonite products require heat. Follow the manufacturer’s recommendation for water temperature.

- Once the bentonite is fully dissolved, pour the solution into a graduated cylinder or volumetric flask. Add winery water until the target volume is reached (1 Liter).

- Transfer the stock solution to a container with an airtight lid and store it in the refrigerator. To aid in resuspension before use, store with a stir bar in the container.

Heat Stability Test/Bentonite trial

- Resuspend the 5% stock solution of bentonite by placing the storage container on a stir plate. If the bentonite has settled to prevent the stir bar from moving, gently shake or stir the solution manually. Once the stir bar can move, allow it to mix while you prepare the wine. The bentonite stock solution must be fully mixed prior to addition to wine for bench trials.

- Determine the amount of 5% stock solution you will need to add to 100mL of wine. A useful technique is to realize that 5% solution has 5 g/100 mL of solution.

- For example, if you plan to test 10 g/hL, 20 g/hL and 30 g/hL of bentonite in a volume of 100ml wine, you will need to add 200 uL, 400 uL and 600 uL of stock solution, respectively.

- For wines that have a suspected high rate of instability (such as Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Gris, Traminette and Petit Manseng), you may choose to first test a wide range (25, 50, 75, 100 g/hL), then do a second test within a smaller range to determine in the precise addition. For example, if stability is reached between 50 and 75 g/hL in the first trial, test 50, 60, 70 g/hL in the second trial.

- Measure 100mL of wine with a graduated cylinder into a small labeled bottle for each treatment plus control. (You will need 4 bottles total for the example given above.) Use a micropipette to add the well-mixed bentonite stock solution and mix. Mixing should mimic the rate of mixing that will occur in the tank. Practically, this is best determined by eye. If no stir plate is available, mixing can be done by inverting the closed bottle (ensure the closure is secure before inverting). Allow the bentonite to settle overnight after mixing.

- The volume of the sample can be adjusted if needed. Re-calculate the volumes of bentonite additions to accommodate a change in base wine volume. However, be aware of the final volume needed for the NTU meter. Allow for a 10% loss of volume during filtration to determine the minimum volume needed.

- After settling, turn on a water bath to 80°C. If a water bath is not available, an immersion circulator (available commercially for kitchen use) can be used. Make sure the temperature gauge is set to Celsius.

- Decant the wine off the settled bentonite into a separate container, then filter. A 0.45 um filter should be used to determine protein stability for wines that will be sterile filtered. Following are two possible methods for filtration:

- If using a syringe filter, insert a 0.45 um filter into the filter housing and secure it. Pull up the wine into the syringe, then screw on the filter and gently depress the plunger. Go slowly, as the filter can burst.

- If using a vacuum pump attached to a side arm flask, attach the Buchner funnel and place a 0.45um filter inside the funnel. Wet the membrane with distilled water and start the vacuum to clear the membrane. Discard the water in the flask. Re-wet the filter with a small amount of the wine sample, start the vacuum to rinse the filter. Discard this wine as well (it is still diluted with residual water from the rinsing). Then, filter the full wine sample.

- Prior to heating, measure the NTU of each sample individually. Each NTU meter will be slightly different, so follow manufacturer’s instructions for use.

- Check the standards to make sure the meter is calibrated. (If the meter is not calibrated, follow the manufacturer’s instructions for calibration.)

- Make sure the sample vials are clean prior to use. If needed, clean the vials with distilled water and a lint-free, scratch-free cloth. Avoid leaving fingerprints on the sides of the vial as this interferes with measurement.

- Rinse the sample vial with a small amount of filtered wine and discard. Then, fill the sample chamber with filtered wine. Read and record the initial NTU for each sample. Return wine the wine to the sample bottle after reading the NTU.

- The initial NTU of filtered wine should be less than 2.0. If the turbidity is higher than this, check the filter and filter again.

- Transfer samples to glass bottles or tubes that can be heated in the water bath. Take care to record the position of each sample in the bath, as markings on glass containers may be removed by hot water and steam.

- Incubate the samples in a warm water bath (80°C) for 30 minutes (or 120 minutes, if you prefer). Make sure the water level goes as far up as the sample in the bottle or tube but does not enter the tube. Use parafilm or tube covers if possible. It is likely the temperature of the bath will drop when the samples are put into the bath. Wait until the bath returns to 80°C before starting the timer.

- After 30 (or 120) minutes, remove tubes from the water bath and allow them to cool to room temperature. Tubes should be allowed to cool for 6 hours to overnight.

- After samples have cooled to room temperature, measure the turbidity again using the same procedure as above. Record the final turbidity.

- Important! Make sure to resuspend any particulates that have settled to the bottom of the tube prior to reading NTU. These are proteins that have come out of solution that should be included in the turbidity number.

- Calculate the change in turbidity by subtracting the initial NTU from the final NTU. It is expected turbidity will rise as a result of heating. Generally, a change of less than 2.0 NTU is considered heat stable.

- To clean, rinse the vials several times with hot water, then several times with distilled water. Dry the vials thoroughly before putting them away.

Measuring for CMC stability

CMC products (like Celstab or Claristar) are commonly used to achieve tartrate stability without having to cold stabilize large tanks of wine. These products require that the wine be protein stable prior to treatment because their addition can trigger protein haze formation. (CMC is a carbohydrate that can complex with protein to cause haze.) Though CMC instability has been reported in rare cases to take as long as 48 hours (with a single reported case at 4 months)(Eglantine Chauffour, personal communication), most instability occurs immediately.

If you plan to use a CMC-based product and want to first test to determine your wine is fully protein stable for this addition, the following protocol is recommended:

- Treat the wine with bentonite to the determined rate. Allow bentonite to settle.

- Take a sample of the bentonite-treated wine. Filter the wine through a 0.45 um filter.

- Measure initial NTU. This number should be less than 2.0.

- Add 1 ml/L CMC product.

- Perform the heat test as described above (80°C for 30-120 minutes).

- Measure the change in NTU from the initial test.

- A difference of less than 2.0 indicates stability.

References

The above protocol was adapted using information from the following sources

(1) Esteruelas, M.; Poinsaut, P.; Sieczkowski, N.; Manteau, S.; Fort, M. F.; Canals, J. M.; Zamora, F. Comparison of Methods for Estimating Protein Stability in White Wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2009, 60 (3), 302–311.

(2) Pocock, K.; Waters, E.; Herderich, M.; Pretorius, I. Protein Stability Tests and Their Effectiveness in Predicting Protein Stability during Storage and Transport A W R I Report. Wine Industry Journal 2018, 23 (2), 40–44.

(3) Weiss, K. C.; Bisson, L. F. Effect of Bentonite Treatment of Grape Juice on Yeast Fermentation. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2002, 53 (1), 28–36.

(4) Iland, P.; Bruer, N.; Edwards, G.; Weeks, S.; Wilkes, E. Chemical Analysis of Grapes and Wine; Patrick Iland Wine Promotions PTY LTD: Campbelltown, Australia, 2004.