Has it ever happened to you? While evaluating a wine, maybe writing a note for tasting or blending, you encounter an odor. Its familiar. Maybe you know when you have smelled it before, or where the odor comes from, or you can name similar odors…. But you cannot name the odor itself. Its like the word is on the tip of your … nose. The “tip-of-the-nose” phenomenon is actually very common, especially when blind tasting a wine1,2.

Sensory expertise can be defined as “the ability to discriminate among different aromas, to recognize aromas when cued, and to describe aromas in wine by free recall”3,4, all skills that are vital when crafting high quality wine. Successful odor identification, according to Cain (1979, quoted in Herz and Engen) includes (1) commonality (2) prolonged odor-name association and (3) supplemental cues. Improving our sensory expertise will mean deliberate practice to name and remember smells.

Why its so hard to remember and name smells

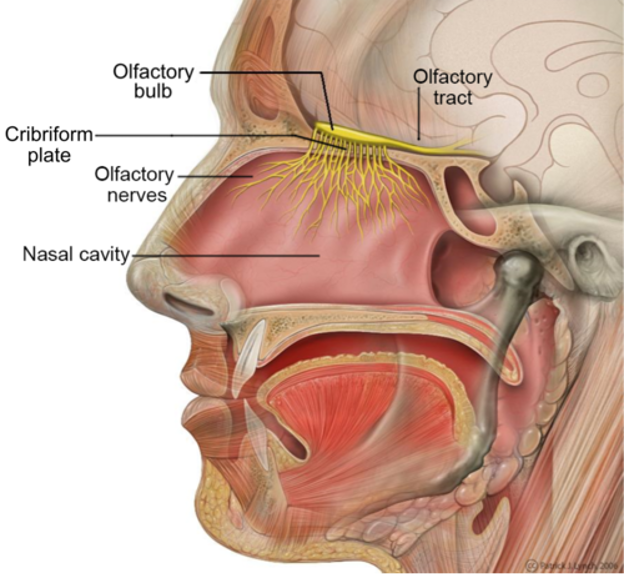

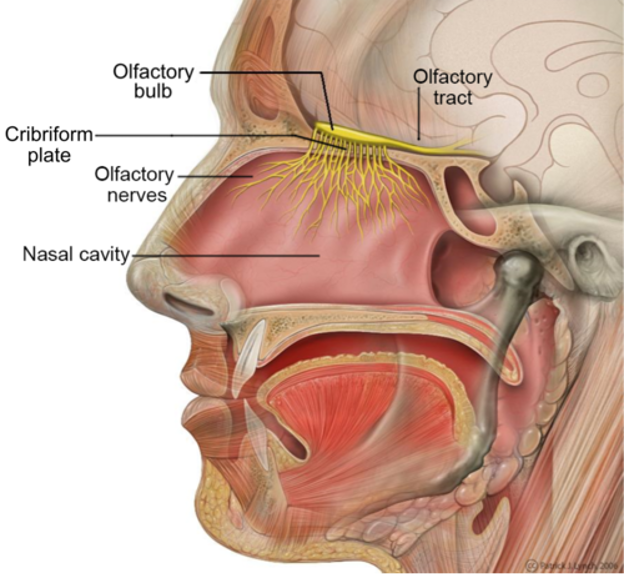

Relative to our other senses, humans are bad at recognizing and naming odors. The overall ability of participants to identify familiar odors in odor recognition research studies is reportd to be less than 50%1,2. There are several reasons that contribute to this lack. The olfactory epithelium, the portion of the nasal cavity that initially perceives odors, as well as the portions of the brain involved in processing odors, are much smaller in humans than in other mammals2. The diversity of odor receptors is also smaller; nearly half of the genes in our genome for odor receptor molecules are non-functional2. The way the brain is wired for odor perception bypasses other the processing centers that would force integration with verbal processing, meaning you can perceive and remember an odor without every identifying it with a word. In most human cultures, but not all, the language we have for odors is relatively impoverished with little redundancy. This means there is less reinforcement from multiple experiences, so words for odors are harder to encode in the brain. It also means that once encoded, there is less interference, and therefore is less likely to be forgotten1.

Figure 1: By Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator - Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustratorFile:Head_olfactory_nerve.jpg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68370471”

In his webinar, Dr. Lahne talked about the process of training a panel of tasters to improve the reliability of data in academic trials using descriptive sensory analysis. Training of that type is focused on one specific question, takes many people and a lot of time, and is well beyond the scope of what we can or need to do in the winery. But as wine professionals, it is still important that we train our palates to better discriminate among flavors and aromas and recognize faults.

How to improve our sensory expertise

As with most endeavors, the best way to improve our sensory expertise is to practice. In his New York Times bestselling book Outliers: The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell5 quotes work done by Dr. K. Anders Ericcson looking at what separated those who were merely good and those who had the potential to be great in their field. The common thread seemed to be time on task, with roughly 10,000 hours needed for mastery. In her New York Times bestselling book Grit: the power of passion and perseverance6, MacArthur Genius Award winner Angela Duckworth picks up this thread and expands upon it by asking Dr. Ericcson why she, a runner since college (surely clocking more than 10,000 hours) has not become an excellent runner. The professor asked her if, when she was running, she was deliberate in her practice. Did she have a goal? Did she measure her time or log her distance? His point was that achieving excellence is not simply about practice but deliberate practice.

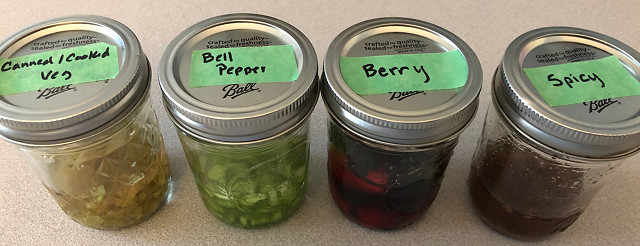

Nobody is suggesting you put in 10,000 hours of sensory training (unless perhaps you plan to sit for your Master Somm exam). However, the idea of deliberate practice is a good take-home for sensory training as well. Many of us have sniffed and swirled a lot of wine in our professional careers. But if we are doing this without any attempt to improve, our sensory skills may be stagnant. A little bit of intentionality may go a long way to honing our palate. In a recent study of sensory training, Lestringent et al3 found that as little as 10 minutes of training on reference standards increased participants ability to describe wine with words. This held true for amateurs, experienced tasters, and even the panel that originally came up with the standards!

Deliberate practice includes goals. What goals should we set for sensory training?

The first goal of sensory training should be to accurately associate odors with their names. When screening participants for a sensory study, Frost and Noble (2002) found no correlation between scores on a wine trivia test and smell association test, meaning wine knowledge does not itself improve sensory performance. When Lestringent et al (2017)4 trained panelists on terms and standards correlating to the second tier of the wine aroma wheel (which are fairly general, terms like spicy, citrus, berry), even experienced and trained tasters averaged less than 160/186 possible points. This immediately after training3. Lest you lose heart, experience did help, here. Consumers scored an average of 120/186.

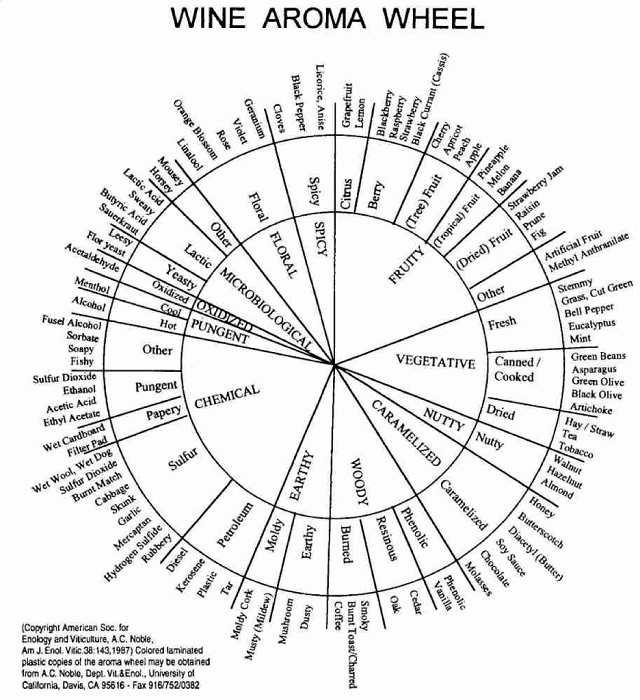

Many terms used for wine are unfamiliar in common vocabulary and can even be cryptic to experienced wine tasters if not defined. The wine aroma wheel includes terms such as sorbate, linalool, and butyric. I only learned what butyric acid smelled like during our sensory workshop at King Family Vineyards in 2019 when Dr. Chang prepared the standard for this compound. When members of my group smelled the standard and discussed its attributes, we agreed it reminded us of parmesan cheese. Based on this shared experience of training with terminology, I now remember both the term and the smell that goes with it.

From: https://www.winecolorado.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Smelling_Wine.png

We cannot achieve a goal of consistently and accurately using terminology unless we know what that term really means. Also, the less familiar an odor is, the less likely we are to be able to find it in our memory1. Deliberate practice introduces us to these stimuli and reinforces that learning with repetition and experience.

Another goal of sensory training is to become more precise and consistent with our terms in order to better communicate with others. Due to the tremendous variation in human anatomy and experience, sensory analysis is fraught with variation. Sensory perception itself begins with signal reception, which for odor means a volatile chemical binds to a protein receptor. Humans have roughly 340 identified genes for odor receptors, any of which contain variants from individual to individual. Genetic differences also alter the number of taste buds (the structures on which these receptors sit) between individuals. Differences in diet, health and environment can alter the number of taste buds that are active (yes, you can literally burn out taste buds with spicy food!). In addition, sensation is additive, so the other odors that are received at the same time may compete for attention by the neurons. Once odors are received, their presence is communicated though the nervous system to the brain. Some nerves fire more readily than others. Once in the brain, the past experiences of the taster will determine if the odor is recognized and how it is labeled. The same odor in a different mixture may be encoded with very different terminology1,2,7.

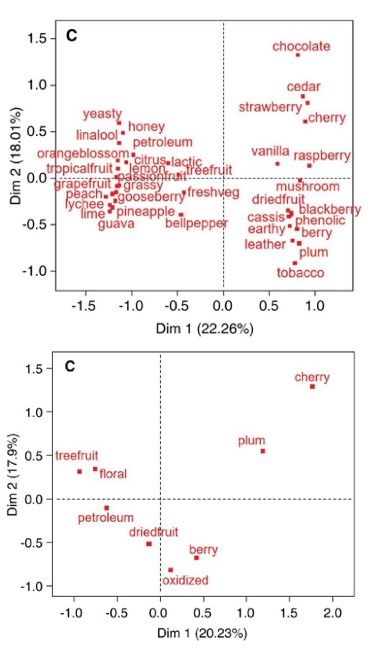

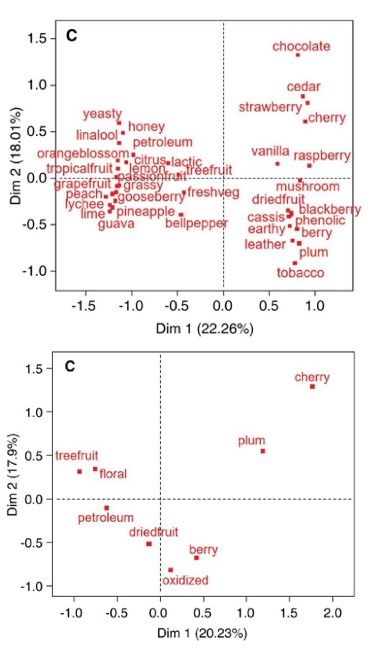

Consensual terms used to describe wines by (1) experienced tasters and (2) trained experienced tasters. From Lestringent et al (2019)

Wine professionals often have a wide experience with odors and flavors, meaning our vocabulary may be very broad. Unfortunately this may lead to the same odor being described with multiple, redundant terms in different circumstances. If one term is used in one situation and a different term in another, it may not be clear the same odor is being referenced. In their comparison of consumers and experienced tasters, Lestringent et al4 found experienced tasters used 36 different terms to discriminate the wines while experienced tasters who had been trained with standards required only 10 for the same discrimination (Figure 1). Training meant that people were more likely to use the same words for the same odor. Sensory training is a way of tying a specific odor to a specific memory and a specific word that all tasters have in common, leading to more accurate and precise odor recognition and recall.

Finding common language allows for better communication with others. Winemakers and staff need to be able to recognize faults and name them with common understood terms to be able to properly treat the issues. Common terminology is also vital to participation in the larger conversation of wine. When explaining the origins of the Wine Aroma Wheel, which was developed to provide common terminology for California winemakers, Ann Noble said “How can you evaluate your own wine against others if you don’t use the same words? (CITATION – TEAGUE).

Sensory training on standards can also help winemakers to better diagnose problems and issues in the winery. Many of the differences in descriptors that people use make no difference in the management of the wine, for example the difference between “black” and “red” raspberries. However, some differences may be relevant to winemaking operations. One example is the term “vegetal”. A wine may be described as vegetal because it has perceptible levels of methoxypyrazine, which smells roughly like green bell pepper. However, this same term can be applied to a wine that has mercaptan (cabbage-y) or DMS (cooked/canned green beans or asparagus). Unfortunately each of these potential flaws leads to a different potential treatment of the wine, and what works for one will not work for another. No amount of aeration will remove the methoxypyrazine (though it may affect the thiols and therefore perception of green pepper, but that is a whole other newsletter….). A similar argument could be used for various terms used to describe microbiological odors. During the development of the Brettanomyces aroma wheel, researchers found several terms that were usually associated with Brettanomyces infection could also be due to lactic acid bacterial infection8.

References

(1) Herz, R. S.; Engen, T. Odor Memory: Review and Analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 1996, 3 (3), 300–313.

(2) Jackson, R. S. Wine Science: Principles and Applications, 4 edition.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2014.

(3) Bowen, J. T. S.; Cantu, A.; Lestringant, P.; Sokolowsky, M.; Heymann, H. Wine Sensory Reference Standards to Align Wine Tasters on a Shared Terminology. Catalyst: Discovery into Practice 2018, 2 (2), 42–49.

(4) Lestringant, P.; Sela-Bowen, J.; Cantu, A.; Sokolowsky, M.; Heymann, H. Exposure to Aroma Reference Standards Alters Participants’ Descriptions of Commercial Red and White Wines. Catalyst: Discovery into Practice 2019, 3 (1), 17–22.

(5) Gladwell, M. Outliers: The Story of Success; Little, Brown, and Co: New York, New York, 2008.

(6) Duckworth, A. Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance; Scribner: New York, 2016.

(7) Urry, L. A.; Cain, M. L.; Wasserman, S. A.; Minorsky, P. V.; Reece, J. B. Campbell Biology (11th Edition); Pearson: New York, 2017.

(8) Joseph, C. M. L.; Albino, E.; Bisson, L. F. Creation and Use of a Brettanomyces Aroma Wheel. Catalyst: Discovery into Practice 2017, 1 (1), 12–20.

(9) Zoecklein, B. Protein Stability Determination in Juice and Wine. Virginia Tech Online Enology Publications 1991.