Vineyard sample preparation and testing

In order to get the most accurate measure of fruit chemistry, it is important to prepare your fruit samples properly and make sure your lab equipment is properly calibrated. Also, there are a few things to remember when measuring Brix, pH and TA on juice.

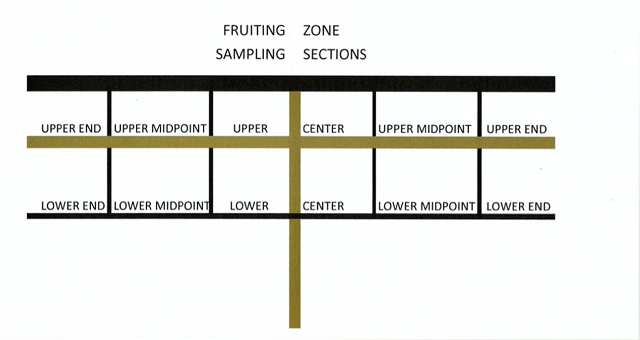

In the field

It is helpful to sample at the same time each day, preferably in the morning. Samples should NOT be kept in a hot car through the day, as they will internally metabolize and change both sugar and acid. Also, when taking vineyard samples be sure to label all samples clearly so that your lab tech (or yourself) will be certain where these grapes came from! It is helpful to keep a kit in your car that includes a Sharpie, plastic ziplock bags (the larger ones, so you can fit a large enough sample to be representative), and a small cooler with an ice pack. No need to freeze the grapes, but just keep them from overheating. (It is also helpful to have some cleansing towelettes. Grapes are sticky.)

In the lab

When you get the grapes to the lab, treat the grapes the same way they will be treated when they are picked. If you will be macerating them on skins after harvest, macerate them on skins in the lab. If you will be whole cluster pressing, then make sure to separate skins and seeds right away. Either way, make sure to macerate fully, attempting to achieve the same pressure each time, without breaking seeds. Studies have found that grapes macerated in the blender have accurate brix but not acids (the pH is 0.2 higher than when macerated by hand).

After you have separate skins from seeds, make sure you allow juice to settle before reading brix with a hydrometer, and before measuring pH and TA. Also, if the juice is fermenting, the TA will be erroneous due to dissolved carbon dioxide, so you will need to degas the sample before you do your reading.

Measuring Brix

Brix is a measure of soluble solids where 1 degree Brix = 1 gram solute in 100 g of juice. In grape juice, sugar makes up roughly 90% of the soluble solids. Hydrometers and refractometers use different methods to measure soluble solids (density vs. bending of light). Both should be compared to standards each day to ensure the device is properly calibrated. Distilled water should give you a measure of zero. Brix standards of 20 and 25 are also available (Enartis), or could be made in the lab, which can also be used to make sure your instruments are giving accurate readings. Most refractometers allow you to turn a dial to set the zero point if it is off. If you are using a digital refractometer, make sure to zero to distilled water, and always make sure your sample well is clean before you calibrate. You should calibrate and check standards every day before you test your samples.

Refractometers and hydrometers are also temperature dependent. Some come with a thermometer that will self correct, but some do not. If your device does not come with a thermometer, tables are available online to determine the correction for your sample temp.

One addition thing to note, if you are using your hydrometer to determine when your fermentation is complete, keep in mind that the hydrometer is reading the density of the liquid relative to the density of water. Alcohol is less dense than water, so as the fermentation proceeds, the hydrometer reading is going down due to both sugar depletion AND alcohol accumulation. A finished wine will have a negative hydrometer reading. How negative the reading is depends on the alcohol of the wine (so Petit Manseng will be more negative than Sauvignon Blanc).

Measuring pH

You must calibrate your pH meter with standards of 4 and 7 at least once per day. Twice per day is better during a long harvest day. pH is a logarithmic scale, which means there is a 10 fold difference between a pH of 3 and pH of 4. When the meter begins to drift, it is time to calibrate again, since often the difference between pH = 3.25 and 3.35 may determine when to harvest.

After you calibrate your pH meter you should re-check with standards. The best standards are in the range that you will be reading. This may include a box wine you have had tested at a commercial lab (also a good standard for other measures such as TA, alcohol, and any enzymatic tests you may be running). Also, 1 gram of cream of tartar (the same thing you use for seeding wines that are being cold stabilized) dissolved in 100 mL distilled water has a pH = 3.56. This is a supersaturated solution, so as long as you have more than 1 gram, you can just scoop without measuring.

pH determination is also temperature dependent. It is best to calibrate your pH meter with standards that are in the same temperature range as you samples. Most pH meters have thermometers that will allow for temperature correction, however samples that are far away from the calibration temperature may not be accurately corrected.

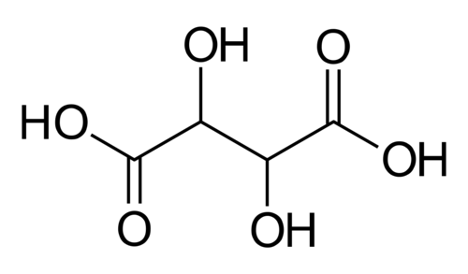

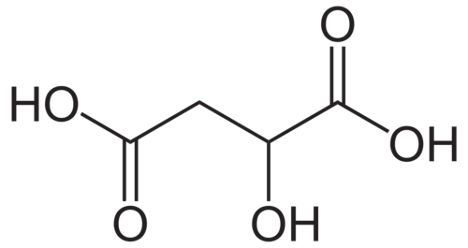

Measuring TA

There are a few things to remember when measuring TA that will help these measurements be more accurate. Make sure your NaOH standards have been checked (weekly) for normality. There is a simple protocol for this. If you would like a copy, feel free to email and I will send you one. If your NaOH has started to lose its strength, your TA numbers will be inaccurate. Make sure you settle the juice samples before you test TA, and your pH probe has been calibrated properly. You will also need to degas any samples that may be fermenting. This includes grape samples that sat too long in someone’s hot car. Carbon dioxide dissolves in grape juice to form carbonic acid, which will give you a higher TA reading. Post fermentation samples need significant degassing to yield reliable readings.

Sensory Evaluation

There are over 700 compounds in mature grapes, some of which contribute to wine quality. Not all of these change at the same rate as sugar during grape ripening. Grape sugars make up 90% of the soluble solids in grapes, but the rest includes important molecules such as tannins, polysaccharides, pigments, acids, protein, potassium and others. Most of the time, these are not measured in traditional grape testing. So, it is important to also taste the juice.

It is important to taste samples successively over time to calibrate your palate to the flavors of unripe, ripe, and overripe juice. It is best to taste the samples before they have oxidized. Juice from grape samples often oxidizes very quickly due to lack of SO2 and the presence of active oxidative enzymes. If you must delay tasting juice, put the juice in the refrigerator to slow down these reactions. However, make sure you have measured the acids and sugar before doing this, as cold temperature affects brix determination and also can cause precipitation of acids.

Many flavor compounds that will be present in wine are in bound forms in juice, and will not be perceived until the enzymatic reactions of the yeast release them. However, as grapes ripen there is an evolution of flavor. Bisson (2001) illustrates the evolution of grape flavors as follows:

Vegetation ----> Herbaceousness ---> Unripe Fruit -----> Red Fruit -----> Black Fruit -----> Jam

In the same paper, she suggests a textural evolution from crisp and juicy to jammy and gummy which coincides with the softening of berries due to changes in their cell walls.

Additional measures of maturity

Though the lab numbers are helpful in tracking fruit ripening, other measures of maturity are also available. Seeds move from green to brown as the tannins are oxidized and lignified. Skins become more extractable and red berries will color the juice faster as cell walls begin to break down. Stems may change color from green to brown, though this may not happen in all varieties in all vintages. Oxidation of juice may become very rapid if fruit is overripe or infected with Botrytis. All this means that the lab numbers should be supplemented with sensory analysis and visual observation of the grapes, both in the vineyard and in the laboratory.

References

Determining Grape Maturity and Fruit Sampling, Ohio State University Extension, 2014

Evaluation for Wine Grape Maturity for Harvesting, Vineyard and Vintage View, 1995

In search of optimal grape maturity, Linda Bisson, Practical Winery and Vineyard Journal, July/Aug 2001